Ancient Improvisation in Paros

In Paros, I explore ancient improvisation through sketches, maps, and interviews with jazz pianist Charu Suri and classicist Armand D'Angour.

Updated August 4, 2025

Naoussa harbor at night. The Kimisis Theotokou Greek Orthodox Church is visible in the background.

I

’ve just arrived on the Greek island of Paros with Jane and Kellan. Paros, shaped like an egg, sits in the center of the Cycladic islands—those 220 islands southeast of Athens which spill out into the Aegean Sea.

Paros, neither particularly remote nor over-touristed, finds its following from Greeks and other Europeans who come for the food scene and the quiet. We’ve come here to explore Paros’ old sundrenched villages—and I’ve come with a very big question on my mind: could an ancient musical improvisational master, akin to a Django Reinhardt, Miles Davis or Jerry Garcia, have traveled through these islands, playing to audiences that sought out live spontaneous composition?

I have always had a distaste for the way modern culture treats the subject, and the way travelogues jump right into Hercules or Plato or the Iliad and Odyssey or the battle of Troy. The over-quoting of Plato bugged me, and the drama and glory and valor of brutal war in films about ancient Greece felt repulsive and indulgent to me.

At Greek restaurants, I was bothered by the worn out iconography lifted from old Greek vases, of frolicking Gods and the robed wealthy. I was never a fan of the faux-marble columns on square box mega-mansions, plastic grape vines and olive leaves.

Paros Door, painted in the color of summer bougainvillea blooms. Featured in my doors and windows of the world gallery.

When I was a freshman in college, I visited the Getty Villa Museum in Malibu which was modeled after the ancient Roman Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, filled to the brim with Greek and Roman antiquities. This sprawling villa, its fountains and pools and frescos, reminded me of my distaste for how we consumed ancient Greek history.

Then, something extraordinary happened, and it changed my life.

While visiting the Getty Villa Museum, I wandered into a small room, maybe it was the smallest room in the entire museum. The room was dark, and only the displays were illuminated: a small collection of Cycladic statuettes and figurines. These figurines looked modern, as if they were carved for an exhibit at MOMA. They looked alien and mysterious. Their simple lines made them elegant and timeless.

But the wall panels explained that these figures were carved in the Bronze Age, some of them five-thousand years old. What’s more, they were carved on small islands in the Aegean Sea, many of them collected from Paros or its small sister island, Anti-Paros. This was not the artwork of wealthy high courts from some classical era, nor was it tied to eras of war or glory. Rather, these figurines appear to have been made by ordinary people living in small windswept island villages. Polished to a perfection by a civilization that was almost completely unknowable, lost to history. This old culture changed little over the millenia, and these figurines, like the culture that made them, also saw only incremental design changes over the millennia.

These figurines reminded me that there was a Greek history for me—the sparsely documented and almost completely unknown story of ordinary people who lived in the far flung locales of the distant past.

My handpainted map of the Cyclades islands. Paros and nearby Naxos, where many of the Cycladic figurines were found, sit near the center of this island group.

In these elegant figurines was no Zeus or Poseidon, but the suggestions of history that felt compelling to me: what did these people eat? How did they fish? Did they travel from island to island? What did their homes look like, and what stories did they tell to their children?

Then, years later in New York, I saw it, the figurine that led me on a life-long itch, an itch which ends in these notes. Marbled Seated Harp Player is a Cycladic figurine known as one of the earliest representations of a musician in art.

Believed to be from 2,800 B.C., and excavated in nearby Naxos Island, this figurine is surprisingly detailed, showing a musician engaged in the act of plucking his stringed instrument. The marble is precisely carved to show the musician’s thumb hitting a string. The musician looks up in the air, as if he is in a state of intense creative output.

For fans of live improvised music, we know this look well. For fans of Phish, it’s called ‘Trey Face’—that awkward look of guitarist Trey Anastasio lost in the magic of improvisation, Looking up, mouth agape, eyes withdrawn, staring blankly into the rafters of the stadium. Or that moment when The Grateful Dead's Jerry Garcia turns his back to the audience, focusing on nothing but the tiny red lights of his rig. In a state of intense improvisation, saxophonist John Coltrane stands hunched, his eyes closed, his face contorted. It looks as if he's dreaming.

Ever since I saw Marbled Seated Harp Player, I have wondered, how were people on tiny far-flung islands playing harps 5,000 years ago? What did that music sound like? And, ultimately, I wanted to confirm my suspicion: that figurine depicts a musician who is improvising, right?

My sketches of various Cycladic figurines, including the two which sparked my lifelong curiousity about live improvised music in the ancient world.

Naoussa and the Improvisations of History

We are staying in the town of Naoussa, on the north coast of Paros. Today, Naoussa is a suave destination, complete with hip clothing shops and young partiers.

Paros attracts its share of Instagram influencers, and you can see them in the crowds, sometimes looking sad and even lonely until the moment they turn their cameras on themselves, only then brightening with huge smiles.

At the center of the old harbor is a 13th century port guard fort, built by the Venetians to protect the commercial trade. In the Venetian era, there would have been two of these towers, tall enough to see far into the Aegean—an early warning against the Aegean’s timeless threat, pirates.

I walk out to the fort on a stone and concrete jetty, enter it through one of its six embrasures and then exit out another, onto a shallow rock reef facing out towards the Aegean.

Beyond the defensive fort, I can see the view that the ancient Naoussans may have seen, and I wonder about whether a small musical group, maybe a duet, or a trio, or even a quartet, might have hitched a ride on some early trading vessel, ready to play to an audience familiar with their group and hungry for new, live melodies.

Before I can imagine that, I have to find out if there might have been performers and audiences that sought out live improvised music so long ago. There is this idea that true improvisation in music is something that was invented, perfected, and perhaps lost in the twentieth century—the Golden Age of Jazz.

Let’s take a step back and define musical improvisation. It is true that any live musical performance has elements of improvisation. The way a singer leans in on a certain sung word, a solo, extended out, modified and played pitch perfect, or the decision by a bandleader to feel the audience and make a snap judgment to alter a song in the setlist. And this would have been true in the ancient past, too, for there is evidence that musical notation, and the role of the composer, was almost absent in ancient history.

For our purposes, we’ll define musical improvisation more narrowly as a group of musicians composing new passages of music on the spot, having a large quiver of musical ideas, learned from classical training, guilds, travel or consumption of diverse and exotic scales, tunings and melodies. Perhaps especially, this includes the ability of bandmembers to listen, build upon and react to the ideas being spun live by fellow bandmates.

If The Beatles are the most successful band measured by pieces of studio music sold around the world, then perhaps Mozart and Beethoven are the most successful musicians if we measure the ubiquitousness of their compositions around the world.

But both musicians saw themselves primarily as live performers, rather than composers, and their compositions were inspired by their live inventions.

Naoussa harbor at sunrise, from the ruins of the Venetian fort.

The Benedictine Monk, Placidus Scharl, who heard Mozart play live, is quoted describing his early years:

Even in the sixth year of his age he would play the most difficult pieces for the pianoforte, of his own invention. He skimmed the octave which his short little fingers could not span, at fascinating speed and with wonderful accuracy. One had only to give him the first subject which came to mind for a fugue or an invention: he would develop it with strange variations and constantly changing passages as long as one wished; he would improvise fugally on a subject for hours, and this fantasia-playing was his greatest passion.

Mozart’s passion was not to compose, but to find the music while playing it. He was not taught how to improvise, he was born with a desire for it.

And he was not the only one. Bach, Handel—almost all of the great composers of history—had a desire and compulsion to perform and create spontaneously. Their compositions which are beloved today are largely the result of piecing together bits from their live improvisations.

Some of these live improvisations have been transcribed to paper and exist in written form today. However, I cannot help to wonder if their most amazing musical moments were performed live, containing fragments of spontaneous beauty that walloped the composed versions, filled with nuance that could never be transcribed to paper, and are now lost to history forever.

If improvisation is natural to some musicians from the classical era, then we can deduce that improvisation is an innate skill shared by some musicians, regardless of era or the trends of the day.

But could advanced improvisation have existed in the ancient past?

Interview with Charu Suri

To explore that question, I reach out to jazz pianist Charu Suri while she is driving with her husband and daughter to the International Singer-Songwriters Association Award ceremony, where she has been nominated for seven awards. Suri has quickly gained an international reputation for her band’s compositions and improvisational jazz performances, which blend’s Western jazz with Eastern musical traditions, including ragas, the world’s oldest known formal mode of improvisation, and a format that produces some of the most enchanting longform improvisations in the world today.

Small fish create dazzling patterns in Naoussa harbor.

Erik: You’ve lived in different places around the world. How did these different continents shape your music?

Charu Suri: I was born in Madurai, India, and then moved to Nigeria at age 5, when my father got a job abroad there as the CEO of a record label, and the bungalow we lived in came with a piano.

My mom basically said ‘you took to the keys like a fish took to water, started playing and never stopped!’

I returned to India at the age of 9, and studied Carnatic music as well as Western classical. So of course, growing up during my formative years in India, I was immersed in ragas and Western classical, and that has shaped my sound completely. In fact, that's how I hear music.

Erik: You are sometimes described as someone who fuses jazz with music traditions from Central Asia like Carnatic music and Sufi music, and of course raga. While such a fusion is definitely novel, isn't borrowing from different traditions at the heart of improvisational music? Doesn’t improvised music need to explore the bounds of sound?

Charu Suri: Yes, at the core, that is exactly what my album has been about all along, bringing together different cultures rooted in the heart of improvisation.

The thing is, they all existed independently and were doing similar things, in their own traditional ways before realizing that they weren't the only ones doing it, but now we are at a stage and position to learn about each of them and pay the proper respect to each tradition.

A view of Naoussa Bay, and the typical refurbished fishing boats used by tourists for day trips.

Erik: Raga is partially a form of improvisation, but it is more than that. Can we talk about the raga in terms of its ancient history?

Charu Suri: The thing to note about a raga is that it is a musical tradition that does not just come from India, but from many eastern cultures: India, Pakistan and to some extent Uzbekistan.

All of these cultures practiced more modal music than Western music, which is more tonal. Modal music is mostly about scales, and these scales are not exactly as conventional as the Western framework. The use of these scales in Ancient Eastern cultures can be microtonal, or semitonal. It can be linear and nonlinear, so the idea is that you jump around these scales, skipping notes.

In a Western scale, if you are playing a scale, you would use every single note. Whereas, in a raga, you may be completely skipping notes and jumping freely around, and when you’re coming back down the scale, you might play all the notes. So, there is a certain formality to the Western scale which the raga defies.

To understand the raga, you have to understand what they were used for. They were used to paint a mood, and in history, that may be rooted in a religious practice, or some other cultural and traditional purpose. Often, a certain raga is associated with a certain type of day. So, when I am playing a raga, I take great care to introduce it as a morning raga, or an afternoon raga.

Erik: What is the difference between how a morning raga and an afternoon raga sounds?

Charu Suri: Well, in a morning raga, you will almost always have major accidentals - the note of a pitch. For example, you have Shudda swara, the natural note. If you are playing an F, the Shudda swara would be F. But the F flat would be Komal swara. And a Teevra swara is the sharp note. But morning ragas are always about the happier, sharpened note. So, the context was that morning was a time to play optimistic music, and the scales of these ragas are simply more joyful and pleasant.

A local couple on moped racing through the main thoroughfare in Naoussa.

Erik: So, an evening raga might be more blue?

Charu Suri: Blue is a great way to describe the evening ragas. They are often more blue and melancholic, but there are exceptions. You can mix it up. An artist can create an aura or texture that is different.

There is great improvisational license in a raga, and yet, a raga is a raga. If you play something, you are going to stay in that raga. In Indian vocal traditions, you will never find something that departs.

Erik: We’re talking about improvisation in the ancient world. But are ragas just a footnote of ancient history?

Charu Suri: No, the raga was absolutely important to the culture. It was part and parcel to the artist and the audience. The artist created a sonic world with these notes and the audience consumed it. It was very much like how we think of as jazz. That’s what we have been doing our whole life—improvisation is the heart and soul of raga.

Erik: Were a lot of scales being created?

Charu Suri: It is almost like a Pandora’s box, because there are so many different cultural and geographic groups, so these people would be making up scales that were based off of older scales that were passed down from generation to generation orally. So, each one would be very different. It would take systemic gathering for it to get carried down.

There are at least 183 ragas that we know exist today, but maybe there are way more out there that have not been documented. They are all over the place. We know the popular ones because they keep getting repeated. But, I am always discovering new ones. Bagesri is a new one I found. It is actually a beautiful raga that is meant to be played late, late evening, as in after midnight or early dawn, and this is a raga which is totally different from anything else. You can’t really appreciate a raga unless you really slow down in the moment of the day in which it is intended to be played.

That is asking a lot for Generation Z and our short attention spans these days, but it is kind of what I want to do in my concerts. To slow down to that particular moment of the day. I can play Chopin in E Flat any day, but these ragas come with tradition.

Erik: Because the Jazz Age is a 20th century phenomenon, I think sometimes we synonymize the invention of improvisation with this era. When was raga invented? What era are we talking about?

Charu Suri: Mostly, the ragas evolved in the 8th or 9th century, There are two clear schools in India, the Hindustani tradition in the North, and the Carnatic tradition in the south, and the ragas are grouped further into garanasm which are styles of schools. But raga goes back further than that. There are some raga traces as early as even the 1st century. Some believe raga goes back further than that, maybe to 500 B.C.

However, there were precursors to the raga going back as far as 4,500 BC. For example, there was the Saam Ghayan, a very well structured mantra that was played during sacrifices and rituals. It wasn't very extensive, only three notes, but it was a good precursor to the raga.

Erik: When a raga musician is improvising, are they thinking differently than when they are just performing, or even composing? Can you describe what is going through your head when you are improvising live?

Charu Suri: For me, everything is lyrical, and so much of it is about feeling. I try to break up my improvisation into mini-fragments, or licks, and then I repeat them and often create patterns, which is what most jazz musicians do. The style of improvisation is very much personal and fluid. I try not to have a preconceived notion of where a piece will go, relying on the music's impetus and pulse and rhythm section interplay to carry me forward. So much of it is about feeling, feeling, feeling!

Erik: How is live spontaneous music different from studio compositions? If one is not better than the other, what is the specific value of improvising to a musician and an audience?

Charu Suri: There is nothing that beats live improvisation! The energy, the feedback from the audience....all of that lends and fuels the fire! Studio albums and compositions are great in their own way, because they allow for excellence and a quieter ambience that allows for better and more quality listening. Each one is different.

So, with the help of Charu Suri, we’ve established a deep history to improvisation in the Ancient East, one that was so widespread in Central Asia, we can only assume it surfaced in other forms in other regions of the world as well.

But then, what about the instruments? Did instruments exist that could make deep, expressive live music?

The Instruments of Lefkes

On the way to the seventeenth-century village of Lefkes, nestled in the low mountains in Paros’ middle, I ask taxi driver Dimitris about the low walls, zigzagging across the landscape. “They look like they could be 500 years old?”

“1,000, at least.”

These drystone walls are stacked on top of each other without the use of mortar, and create a pattern of terraced landscapes across much of the Cyclades, making otherwise infertile land cultivable.

Cycladic islands typically see rain only in winter, but that rain comes down fast and hard, resulting in the constant threat of flooding. But the carefully placed stone bricks, wedged and stacked precisely together, holds moisture in the terraced hills, allowing rainwater to release slowly throughout the growing season.

“When I was a kid, I worked on maintaining those walls. It is back-breaking work. But do you know, these walls also depict private property, and even though it looks like they are random, the government uses them to know which family owns what land. There are precise logs about property ownership. These records are sometimes a thousand years old!”

I ask Dimitris about the sheer-white bench wall cut from the terraced olive-grove and pine laden hillside.

A small alley in Lefkes, Greece leads to quiet neighborhoods.

It’s a small marble quarry, he explains, abandoned because continuing to mine there would threaten a house nestled in the rocky terrain above.

Such small quarries still exist on Paros, but the most productive mines, built just a few miles from here, are long depleted and abandoned.

The semi-translucent white marble of Paros kept the island on the map in ancient Greek history. Among the most coveted in history, Parian marble was mined on and off from 600 BC until all the quarries were depleted by the nineteenth century. Parian marble was used in time’s most treasured statues such as Venus de' Medici. The marble was also used to build The Acropolis and the Temple of Zeus. It had a unique translucence and rigidity which made it the most sought after in ancient history.

Seeing the white marble reminds me of those Cycladic musician figurines, most of which were also made from the marble of Paros, and other nearby Cycladic islands, although upwards of three-thousand years prior.

Like the famous antiquities made of Parian marble, the Cycladic figurines were carved and then polished to precise perfection. The difference is that while the famous antiquities were made in ages of great wealth, patronage and culture supporting great works of art, nobody knows what purpose the much more ancient Cycladic figurines served.

These figurines were very small, often about six inches tall, and could not stand upright on their own. They were painted, and likely represented real people rather than Gods. Maybe there was a religious aspect to these figurines, but I see them as more likely serving a more ordinary purpose: Cycladic figurines were artworks held by ordinary people in ordinary households.

Like our obsession with faces, celebrity, beauty and representations of family, these figurines were likely just the same—everyday compositions of those we cherished, found beautiful, or whose fertility or safety in childbirth we prayed for. It wasn’t that they were for one thing—like funerary icons, rather, they were the ancient Cyclades’ equivalent of photographs, serving diverse purposes.

It is true that most Cycladic figurines are female, and that there are suggestions in the forms of fertility and childbearing. But what do we make of the male harp player, or the male aulos player, both seemingly depicted as lost in musical improvisation?

Blue-domed Byzantine Church in Lefkes, Paros.

Is it possible that these elegant and mysterious figurines were not religious icons at all, but rather more akin to family photos, surfer girl posters, or Instagram art?

In my college days, I can recall that if you would tour a representative set of male dorm rooms, you would find some posters depicting women humming with the arc of fertility. You might find some photos depicting people back home—a family, a brother or sister, or some friends. There may be a few photos of sports figures. Possibly more so, you might see band posters, music posters, and of course you would also find posters depicting musicians (Mine was the 1967 black and white photo of Jimi Hendrix, smoking a cigarette).

If my conjecture is plausible, then what do we make of the depicted Cycladic musicians? Were these musician figurines religious icons? Or fertility icons? Or is it more likely these are posters of a Jimi Hendrix, only 5,000 years ago?

Jimi Hendrix had an expressive instrument, an electric guitar, which is not actually a guitar, but an instrument which resembles a stringed instrument that existed in one form or another for thousands of years.

One thing we all associate with Jimi Hendrix was his prodigious use of the whammy bar, a little arm extending out from the instrument’s bridge, allowing him the ability to temporarily change pitch.

Such vibrato systems produced a number of hallmark sounds that helped propel music into the modern era. But without whammy bars and other such modern inventions, how could ancient music have been adequately expressive enough to match accomplished improvisation?

What did that harp depicted in Cycladic figurines sound like? And that flute, or, rather, aulos?

Well, actually, it turns out ancient whammy bars did exist in Ancient Greece.

Maybe the best way to resolve this is to put together the instruments of a small traveling band. Rather than just asking this question for a specific period, we’ll consider instruments from every period in ancient history, from the early Bronze Age of 3,300 B.C. to the Athenian era of about 400 B.C.

Instrument One: Aulos

One of the Cycladic figurines depicts an aulos player. Since this instrument is represented in one of the earliest Cycladic figurines, and is known from throughout ancient Greek history, and ubiquitous in the Athenian era, we can consider this a very likely instrument to appear in an ancient quartet.

The aulos, a double-reeded instrument, is no longer played by musicians in the modern world, and only recently are musical historians starting to put together how it might have been used, although good archaeological specimens exist and depictions of it abound in art. Sometimes incorrectly referred to as a flute, this instrument looked like two flutes extending out from dual-reeded mouthpieces.

The aulos likely played only a handful of notes, but its power was in its unusual, haunting tones, and it could produce an enormous range of notes and sounds. Sometimes, it probably served a purpose similar to the Scottish bagpipe; setting a tone; creating a constant drone to which the other instruments could play over. But it was also an expressive instrument in its own right, and, very importantly, it was loud. Its melodies could accompany an entire chorus.

An aulos would have been a perfect instrument for a traveling musician, but I suspect that an aulos player, an aulette, would have been comfortable with other wind instruments. In fact, the syrinx, or pan flute, was invented in the Cycladic islands around the same time as the oldest known Cycladic figurines. I will propose that a professional traveling aulette also played a flute or a syrinx.

Instrument Two: Kithara

The speed in which new inventions or discoveries could spread around the world in ancient times can be baffling. While stringed instruments were likely popularized in Mesopotamia around 3,500 BC, the harps that were depicted in Cycladic figurines had a unique shape, and featured design differences from the harps of the East.

Since archaeologists have discovered harp players depicted in the Cyclades as far back as 2,800 B.C., and that these harps had already evolved considerably from the forms found in the East, we can assume these instruments started flowing out of the East, through Anatolia and into the Mediterranean , almost instantly.

In fact, the Aegean region of the Mediterranean was the primary contact point between the East and the West: Anatolia, or present-day Turkey, is just a hop and skip from the Cycladic Islands. There is no other similar geographic contact point between the East and West.

The island civilizations produced here in the Aegean were trading civilisations, and instruments from the East were flowing freely and easily into the Aegean.

Stringed instruments were evolving all over the Old World. Lutes (a broad categorization of stringed instruments which look like guitars or ouds) were evolving in Mesopotamia, and lyres (which look like handheld harps), were being developed in Egypt. Perhaps most importantly, there was considerable design experimentation happening across the ancient world with all these broad instrument groups.

Today, if you walk into an instrument shop, and you and remember these notes, you may be surprised by the diversity of commercially saleable stringed instruments: guitars, basses, ukuleles, violins, banjos, mandolins, and perhaps a few more specialty instruments, like an African oud or a zither.

But if there were a giant music store that collected all the types of stringed instruments of the ancient old world, it would be the size of a mall; thousands of unique variations on the lute, the lyre and the harp.

Of all this diversity, there was one instrument that had become the choice instrument in the Athenian era of Greece—the kithara. This instrument resembled a handheld lyre, but with a large soundbox and four to seven gut strings. It was built with much more complexity than the more pastoral lyres, and was celebrated as the instrument of choice for virtuoso performers.

No specimens of this ancient instrument exist today, although by studying the non-technical paintings that depicted them, music historians have built replicas that have helped to understand how they were used.

Quiet alleyway in Lefkes, Paros.

A kithara, we now believe, had advanced features that made it an exceptionally expressive instrument. It is believed that each instrument was built for the specific kitharode musician, constructed to fit his body shape and size. Wearing the heavy instrument via a strap, he could at once play and alter the sound of the instrument: the kithara featured a metal bar along its top, allowing the kitharode the ability to bend the pitch, like a whammy bar.

This instrument was likely invented only in the final Athenian era of Greece, but it was preceded by earlier professional lyres. So, our second instrument is either a kithara, or an earlier prototype. Regardless, such a professional lyre would have brought a big, exciting sound as both a rhythm and lead instrument. The kithara, of which our word guitar stems, would have been ubiquitous in Athenian concerts and plays, often played by the star musician, or used by solo performers.

Instrument 3: Tympanum Hand-Drum

Percussion in Ancient Greece came in very different varieties than how we perceive it today. Many of the percussion instruments were small, ringing metal objects, similar to castanets. But a traveling percussionist would have been drawn to the hand-drums such as tympanums and tambourines. A tympanum hand-drum would be an ideal instrument for a percussionist who needed a hardy travel instrument that created enough volume in a variety of ancient environments.

While percussion's role in the Ancient Mediterranean was small, such instruments would be the perfect complement for a singing poet.

An imaginary instrument superstore of the ancient world would have yielded thousands of diverse instruments, including unimaginable diversity of panduras and other lute-style instruments, influenced and imported from the dry world of Africa and Mesopotamia or left to evolve into new shapes and styles in isolated islands.

Instrument 4: Pandura

Every virtuosic band has its improvisational leader—this is that musician who appears in world history only so often, and who just sees notes in front of her, and perhaps whose head is so filled with musical ideas, she just has to just get them out into the sonic universe.

Compare our earlier discussion of Mozart, dancing around the pianoforte, to the twentieth-century guitarist Django Reinhardt, and it sounds like they have something rare in common. Writes Ian Cruikshank of Reinhardt, “His hugely innovative technique included, on a grand scale, such unheard of devices as melodies played in octaves, tremolo chords with shifting notes that sounded like whole horn sections, a complete array of natural and artificial harmonics, highly charged dissonances, super-fast chromatic runs from the open bass strings to the highest notes on the 1st string, an unbelievably flexible and driving right-hand, two and three octave arpeggios, advanced and unconventional chords and a use of the flattened fifth that predated be-bop by a decade.”

So, if a successful improvisational band needs its Mozart or Reinhardt, what instrument did they play? This virtuoso may have passed up the kithara, for its weight and its limitations.

While we associate only certain instruments with Ancient Greece, all of the instruments of the Ancient world could have passed through Ancient Greece, including a variety of African ouds, bolons and koras, and the many strange harps, lutes and lyres of Egypt, where much of the early evolution of stringed instruments occurred.

Arched alleyway in Lefkes, Paros.

One instrument that appeared in Ancient Greece was the pandura. This was a long-necked lute with three or four strings, and a small resonating chamber. This instrument is depicted in sculptures and artwork throughout the Mediterranean , the Levant and North Africa as an instrument that was lightweight, ideal for a musician teaming with musical ideas.

Perhaps our virtuoso doesn’t use a pandura, per se, but some unknown cousin of it. Some lightweight, expressive, foreign instrument with a fretboard that can dance and move with the ideas of its master.

Our imaginary quartet then is made up of four musicians. We have an aulete, who lays down a droning pitch with an aulos wind instrument. We have a kitharode, who plays supporting rhythms and leads on the advanced kithara lyre. We have a percussionist with an assortment of hand drums, and our group is led by a Pandura-lute master.

Now that we have our band, how do we know whether they could have traveled the Mediterranean? How did they get around, was it safe or accepted, especially for foreign or female musicians? And was there a willing audience outside of the densest population centers?

Stunning alley in Lefkes, Paros.

Piso Livadi and Ancient Travel in the Mediterranean

Jane and I walk from Lefkes down to the coastal village of Piso Livadi on a hot, dry morning.

The village wraps around a shallow-water half-moon harbor, showing off its mix of small, anchored fishing boats.

From the short promenade, I can just barely make out nearby Naxos Island, and I wonder how easy or safe it would be to motor across to the quiet, rocky beaches of that much larger island.

Of course, I am also thinking about our imaginary quartet, and whether it would have been conceivable for traveling musicians to move safely and reliably from city to city, island to island, two-thousand, three-thousand or even five-thousand years ago.

Ancient mariners of the Mediterranean knew that there was a season for ship travel: the seas were reliable and calm from May through September. Today’s view of this Aegean passage is proof: glass water, a gentle breeze at sea.

To understand sea travel in the Mediterranean, let’s recall the Pacific Ocean, where hominids first jumped across large bodies of water, to islands in Indonesia, to Australia and beyond, hundreds of thousands of years ago.

In Cycladic towns, octopus is left to dry in front of restaurants as a way to attract attention to the menu. In the age of Instagram, these displays invite hundreds of photographs, flies, and curious fingers.

We tend to think of water as a barrier to travel, but archaeologists now believe that the settlement of the Mediterranean resembled the settlement of the Pacific more than we ever imagined: early paleolithic navigators weren’t just accidentally drifting this sea, but actively navigating it; colonizing new islands or lands in pursuit of new opportunity.

Paleolithic seafarers of the Mediterranean, whether homo sapien or some other hominid, had a distinct advantage over those of the Pacific: the coastlines are mountainous and therefore easy to see from far away. In the Mediterranean, you can see land from almost any point, except for the very middle of it, at its widest and least important points. Land is visible from virtually any point in the seas of the East, and especially the Aegean, where islands and protruding landmasses abound.

It is no wonder, then, that there is almost no evidence of navigational techniques or maps from the ancient Mediterranean—no use for either.

The first substantial boats to appear in the Mediterranean were likely based on the technology that had been evolving along the Nile—large log rafts. For many thousands of years in the Paleolithic and Neolithic, this was the likely mode of transport as people (or perhaps hominids in general) settled hundreds of islands in the sea.

There just is not enough evidence of ancient boats and ships to know how the earliest Mediterranean sea travel worked. We do know, however, that the sail came to the eastern Mediterranean in about 3,000 B.C., and that date correlates well to almost everything we’ve discussed so far.

3,000 B.C. is the timeframe for when these early Cycladic figurines began to appear, and it’s also the date for when harps, lutes, lyres and aulos began appearing throughout the Aegean and Mediterranean.

An alley cat in Naoussa. After visiting Paros, I was able to publish my alley cats page, which I began to work on ten years ago.

The advent of sailing ships, then, was essential to our timeline. During this time, civilizations along the Nile and Mesopotamia were seeing wealthy classes appear as these civilizations became more advanced. These classes began to desire specialized luxury goods from abroad: high quality cloth, exotic woods, olive oils, manufactured goods. It is on these ships that instruments (and musical styles, modes and theories) began to float from Egypt and Mesopotamia to new lands.

Ancient Greece is not known for its roads. But this is because transportation was conducted almost entirely on the sea—Greece is so endowed with elaborate serpentine coasts that it has more total coastline mileage than the United States.

The Mediterranean's first true civilization, the Minoan Civilization, began to thrive on the large Greek island of Crete, and their civilization took advantage of opportunities posed by the burgeoning desire for exotic goods across the Mediterranean. By 2,000 B.C., the Minoans were developing advanced seafaring techniques. Established trade routes were connecting Crete to Italy, mainland Greece, Egypt and Lebanon.

If you look at the sea routes taken by the Apostle Paul in the first century A.D., they look remarkably similar to the trade routes established by the Minoans two-thousand years before. This is likely not a coincidence: While much changed politically in the Mediterranean in those two thousand years, and countries entered long periods of darkness, sea travel was evolving across the sea with each century, regardless of the political turmoil of any given era.

If you could stand on a hilltop overlooking the Cyclades Islands in, say, the earliest years of Ancient Greece’s classical period, perhaps around 800 BC, on a clear summer day, you would likely see dozens of white sails spread out across the horizon.

In the warm summer season, when the sea is calm enough for regular and safe sailings in the Mediterranean , the water is often crystal clear.

These were not warships, training their oarsmen, but foreign trading vessels; perhaps they were those efficient and well-built Phoenician sailing ships that took the best features from Egyptian and Greek oar-and-sail boats.

Looking out at these billowing sails, you would understand that almost all of them were foreign: in the ancient world, captains were like sole proprietors, buying and selling goods at each port they visited, encouraged by the ports through the lure of tariffs.

Travelers would have little trouble negotiating their way aboard the many merchant vessels moving along the coast.

In Greece’s classical period, travel among cities, not for the purpose of business or medicine or trade, but for the sake of travel, was encouraged. During this lengthy period, large festivals and competitions, precursors to events like the Olympics, sprung up across Greece. The festivals encouraged regular travels to visit new cities, but they also offered a reason to travel specifically for musicians. Back then, festivals were not just about the sports, but the arts, and chief among the arts in Greek culture was music. Musicians would be encouraged to travel to and compete in musical duels.

One musician, Terpander, known as the father of Greek music, was active in the seventh century B.C..

Terpander is among the few, and the earliest, of ancient Greek musicians who we know about. While he is known for primarily for his accomplishments in modernizing and systemizing the music of the Aegean—perhaps making him the father of Western musical theory—for our purposes, we have a sparse record of a musical genius who made technological changes to his instrument of choice, the kithara, and traveled often, moving from region to region, country to country, and performing live in disparate regions of the Aegean.

Detail from a typical Cycladic church on the island of Paros.

Terpander was born on the island of Lesbos, and his fame in the Aegean began there, proving that famous musicians were not known only locally.

Our scant record of Terpander’s life confirms one important detail for these notes. If we have a record of only one musician from this era, we can assume that there are hundreds or even thousands of similar musicians in the Aegean whose behavior would have been similar.

We know that Terpander traveled often to festivals or music competitions in disparate regions of the Aegean, often winning them. As a kitharode, we would play his reconstructed instrument - not the usual 4-strings, but a completely reinvented 7-string variant.

If there was one Terpander who often won festival competitions, there were hundreds of other performers, traveling, performing, competing and gaining musical fame from island to island, country to country.

Was Terpander jamming? Was he winning competitions for advanced and intricate instrumentals, invented on the spot? Or was he singing and strumming the ancient equivalent of bar songs? My hunch is that it was likely a bit of both. Any musician who reinvents an instrument and systemizes the music of an entire region is not interested only in playing popular songs. I don’t think Terpander is the improvisational master we’re looking for. Rather, we know this musician lurked anonymously among the same travel routes Terpander would have taken.

Now we know that musicians could travel, did travel, had a reason to play far and wide, and had audiences waiting for them. We can also imagine how they traveled—by merchant ship, as paying guests of entrepreneurial captains.

So we only have one question remaining. How might improvisation have sounded thousands of years ago?

Detail of a door in the mountain town of Lefkes.

The Performance in Paros Park

Dimitris drops Kellan and I off near Paros Park, a three-pronged peninsula forming the northwestern edge of the Bay of Naoussa. Trails fan out from the entrance of the park, offering access to arid cliffs, coastal wildflowers and the scent of familiar herbs.

The late-sleepers of summer travel have yet to wake, and so we are the first to interrupt the lizards and geckos of the peninsula as they warm themselves in the morning sun.

Near the entrance to the peninsula is a small amphitheater, cut into the side of the rocky terrain and in the design of ancient Greek and Roman sloped theaters. I can imagine how, on a still summer night, no electric amplification would be necessary.

This is a modern amphitheater, but there were almost certainly similar amphitheaters built in the ancient cities of Paros. It is easy to stand in the circular stone stage and imagine a quartet, recently arrived and prepared to perform. But what did they sound like? Could complex improvisations—magical live music—with notes as crisp as Mozart on a pianoforte thousands of years later—have actually played out in an amphitheater like this one?

Kellan and I continue on, along a trail cut into the hillside, meandering above crystal clear bays. We make our way to a small beach, and I pull my packraft out of the backpack and inflate it. I am out on the water in minutes, while Kellan wanders along the rocky shore.

I find myself floating above a rock reef surrounded by a large seaweed forest, and I shuffle myself out of the packraft into the water, peering at small schools of fish. I float beneath my packraft for as long as I can, drifting with the current until I pass Kellan, who is looking at something on the shore.

The shoreline of Paros Park, where Kellan found an 18th century plank from a Russian ship.

I crawl out of the water onto the small rock jetty where Kellan is crouched down. “What is this?” he asks. “Is this part of a shipwreck?”

I pick up the delicate wood, which flakes in my fingers. I can see that partially buried in sand and rock is an old wooden plank, uncovered by Kellan while looking for shells. I dismiss the possibility, but will later learn that the wooden remains of a Russian fleet from the 18th century are still found on the shores of Paros Park.

Sure, there are yachts crowding this bay now, and sure there were Russian ships here hundreds of years ago, but there is also evidence on this peninsula of advanced maritime civilizations from thousands of years ago.

Not far from the amphitheater are the sparse remains of a Mycenaean city, built in the thirteenth century B.C. During that time, this bay would have been filled to the brim with ships too—perhaps long, elegant biremes, loaded with goods from ports as wide-reaching as present day Italy, Egypt, Israel and Turkey.

Paros passed through many hands in ancient history—the Minoans, the Mycenaeans, the Ionians, the Arcadians—in most of history, Paros was no sleepy backwater. These were advanced maritime trading civilizations, and Paros, during many of these ages, was among the wealthiest in the Mediterranean, rich from the island’s prized marble.

A traveling musical quartet might have slipped off a Mycenaean trading vessel right here, in what would have been a natural protected port. If there were cultural circuits that lured musicians like Terpander to distant lands, Paros’ bustling coastal settlements would be a natural part of those routes.

Our quartet would likely have walked down a stony path much like the trail we used to get to this beach. Civilization, with homes and buildings built of thick, pale stone, would have been nearby.

A Roughtail Rock Agama rests on a boulder in Paros Park, not far from a small amphitheatre.

Improvising musicians talk often about their favorite venues—certain places are inspiring, or comfortable, or endowed with pin-drop acoustics. Would this ancient quartet have been inspired by the turquoise bay, the docked ships, the fragrant island air? And what are they preparing to play? What will their performance sound like?

The fact that Terpander was from Lesbos is probably not coincidental. Lesbos, even more so than the Cyclades, is just a hop and a jump from present-day Turkey. Back then, Anatolia, like all of the civilizations of the Near East, was known for its deep musical traditions. While we think of Terpander as the father of Greek music, he was actually an expert of the musical theories and scales and modes of Greece and Anatolia, and he systemized the modes. These ancient modes, variants of which are still used today were consolidated down from perhaps thousands of different scales and modes to dorian, hypodorian, phrygian, hypophrygian, lydian, hypolydian, and mixolydian.

These modes, which are like subtle changes in the steps of a scale, create spectacularly different moods. To the Athenians, a certain mode might be associated with a very specific time or occasion. For example, the dorian mode was thought to be associated with warfare and battle, and would have been used to drum up morale and nationalistic pride. Other scales represented the exotic, or the somber.

In today’s improvisation, musicians funnel through these modes to illicit broad emotions, mixing up the haunting with the triumphant and joyful. When Miles Davis and John Coltrane recorded the improvised So What, they were employing the dorian mode — perhap as far a sound from war and conquest as possible, but still based on a foundation created 2,400 years ago.

But the way that Greeks associated modes with specific emotions starts to sound like the way Charu Suri described raga modes —hundreds of modes established over thousands of years, mixed up, passed around, perfected, changed.

So if Terpander systemized the modes of the eastern Mediterranean, then surely there was some long period before then of a wild west of scales and modes. Maybe the ancient Mediterranean held a painter’s palette of musical ideas to draw from. Perhaps, while we can easily point out the ways that musical expression is more advanced today, maybe there were actually tools in a musician’s kit that existed then, which are lost today.

When a musician today plays a piano, they have the major notes—the white keys, and the minor notes—the black keys. But if a theoretical piano existed in ancient Greece, it would have had notes between the black and white keys — quarter steps, like little tiny gray piano keys, that in our age are difficult to fathom. Some believe these quarter steps helped musician modulate into new keys, shifting in ways impossible today. Advanced modulation is considered a cornerstone of advanced improvisation. Again, a sign that musicians had essential elements to perform live spontaneous music with depth and complexity.

At Paros Park, I sense that I am beginning to piece together the answers I had sought for most of my life. Like millions of others of fans of live improvised music, we cling to our taped recordings of our contemporary jazz and rock improvisations. We know Miles Davis’ Agharta and Pangaea performances in Japan like the back of our hand. We recite the highlights of the Grateful Dead’s entire 1974 summer tour, show by show. We have heard 13 versions of John Coltrane playing My Favorite Things. We are hungry for more, and we often ask, what did we miss? What else is out there? For fans of live improvisation, then, it’s really the most magnificent question of them all—what did we miss over the span of time? Where will improvisation go from here?

Still, while standing here near this Paros amphitheatre, I feel like my quest still contains deep gaps—and, am I extrapolating? Hoping to find the right answer?

Interview with Greek Classicist Armand D'Angour

At the end of my journey, I reach out to Oxford Professor Armand D'Angour, who wrote ancient Greek odes for the 2004 Olympics in Athens and the 2012 Olympics in London, and who is considered the world’s most accomplished scholar of ancient Greek music.

Erik: Can you tell me a little about your own path to learning about ancient Greek music? Did your career as a cellist inform your academic interest in ancient Greek music?

Armand D'Angour: I am trained in piano and cello, and so my musical career undoubtedly influenced my eventual decision to work on ancient music. In particular, ancient rhythms have been poorly understood by scholars bent on trying to establish 'metrical' accuracy. But metre was just a way of recording musical rhythm in practice, but it is treated as a terminologically complex theoretical discipline. The important thing for a Western trained musician to understand is that ancient Greek music is not to be judged by the same criteria as our highly developed tradition. Far better to think as an ethnomusicologist, say one who has worked with folk traditions in the Balkans, Bali, Turkey and China. Tuning was not equally tempered, harmonies were not chordal, and so on.

Narrow alley in the small traditional village of Marpissa, population 580. Marpissa lies adjacent to a cave where some of Paros' most ancient antiquities were discovered.

Erik: You’ve collaborated with musicians to explore the sounds of ancient Greece. In your own words, what does that music sound like?

Armand D'Angour: To ask what the music sounded like is a bit like asking what does Western music sounds like? Are we asking about a Bach cantata or about Heavy Metal? About a Beethoven symphony or about a jazz solo on sax? There would have been a huge range of ancient musical expression, most of which is lost. The surviving notated documents range roughly from the fifth century BC to the 4th century AD. Only 60 of them in a span of 900 years, and mostly very fragmentary.

What I have tried to get from the documents is a sense of the idiom of ancient harmony and melody. For example, did they move in large or small intervals, did they have a sense of tonal center, did they sound major or minor, in our terms, did they work differently with different tempi and tunings.

Ancient authors considered a clear, penetrating sound to be important for music. Soft music was for personal pleasure, public music needed to be loud. We also have many indications that music had a strong effect on listeners. So what does some of the music sound like? Exciting, solemn, urgent, soothing, mystical, rough - depending on which pieces you go for.

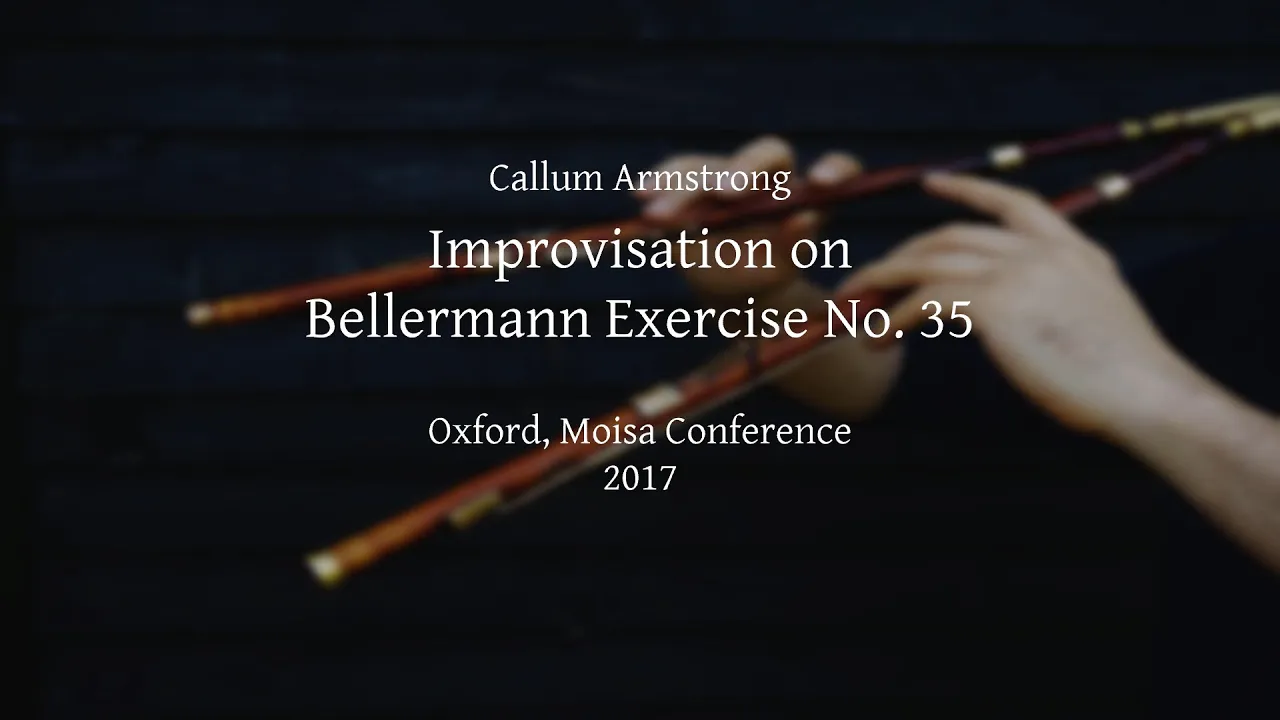

Erik: What do you think ancient Greek improvisation sounded like? When demonstrating ancient instruments, academics often make the music sound dull and lifeless. But then we hear a musician like Callum Armstrong play the aulos, and then it sounds like ancient musical improvisation might have been complex and inventive? Is he just employing modern music theory to an ancient instrument?

Armand D'Angour: As you know, to hear some fantastically powerful improvisation on the aulos, listen to how Armstrong has mastered that difficult instrument and improvises brilliantly. Of course some Greek musicians were able to do on that instrument whatever a modern maestro can, and more, but they would not have used those particular harmonic choices. Callum is a Gaelic piper among other things. They would have improvised according to their own harmonic and melodic idioms.

Erik: Is it possible to reconstruct the rhythms and melodies of ancient Greece?

Armand D'Angour: It is possible to say what the rhythms of much of Greek poetry were by analyzing the meters. It is also possible to invent melodies using what we know of ancient modes and the way they were used.

Erik: Can you tell me a little about how a small musical group might have played together? For example, is it plausible that a quartet might have existed, employing instruments like an aulos, kithara, pandura and percussion?

Armand D'Angour: In the early 5th century, Pindar talks of a combination of aulos and strings with voices. Other authors indicate similar 'sumphoniai'. The Greeks must have experimented with all kinds of instrumental groupings, though there is little hard evidence until much later. I have no doubt personally that they tried all sorts of combinations of instruments, such as the ones you suggest.

Erik: Musicians were encouraged to travel from city to city to compete in festivals. Were there enough such competitions to sustain the livelihood of a traveling musician? Otherwise, do we know whether musicians traveled to perform outside of these festivals?

Armand D'Angour: There were numerous competitions, but also numerous ceremonies, rituals, events, and entertainments in classical and later times at which musicians were expected to play, including informal occasions such as drinking parties - the symposia, which in 5th century Athens demanded the presence of women pipers, known as auletrides. We know of musicians traveling to perform at the panhellenic games. At the Pythian Games there were competitions for solo aulos, at which the story of Apollo killing the dragon was a key event, with pipers competing to play solos imitating the drama. Pindar's 12th Pythian Ode celebrates one of the winners, Midas of Akragas, which is in Sicily. We must imagine that there were a lot of traveling musicians. An inscription in Asia Minor even records a convention of musicians, perhaps from across the Greek world.

Erik: There was obviously a renaissance for music in the classical and Athenian eras of Greece, where a lot of music theory was systemized. But I wonder if there were musical ideas, scales and modes that may have drifted through the Mediterranean and that are now lost to history?

Armand D'Angour: In oral cultures, most music is improvisational or at least partly so. The ancient Greeks had no recording and limited use of notation, so there could be little accurate repetition of musical pieces across decades and centuries, and over thousands of square miles of territory. Every time something was played, it could have different tempi, tuning, and resources, and it would be up to individual musicians to make their pieces or songs appealing to their audience.

We know of groups of musicians traveling around venues. For example, choruses of victory odes or of drama, such as the Actors of Dionysus, moving to different locations and theaters. In classical times the harmonic system was such that it seems likely that they could be instructed by a poet such as Pindar to sing a song in a particular mode, such as in the Dorian or Lydian mode, and that it was then up to individuals such as a chorus leader to decide exactly how to melodise the words.

The systematization of the modes in the fourth century BC is a marvel, considering that it emerged from a practical performance context in which gapped scales, like the pentatonic scale, were commonly used. Greek theoreticians filled in the gaps and produced something like a comprehensive theory of musical harmony. That doesn't mean it was ever fully exploited, but it certainly allowed for a wide range of musical expression and was transmitted in different forms to Byzantium, the Arab world and even India. I don't think much theory is lost to us, but I am sure that a vast amount of the practical applications of that comprehensive musical system has vanished, including pretty well everything to do with the Romans' use of melody and harmony for hundreds of years from the third century BC to the tenth century AD and beyond. So we can reconstruct on the basis of what we know, happily assuming that many ancients did the same for centuries.

The narrow alleys in Paros are so small that garbage trucks must be narrow enough to navigate them. I sketched this Piaggio Ape 50 Van in Naoussa.

The Ferry to Athens

We are on the giant ferry back to Athens. Jane and Kellan are sitting inside, sipping on drinks. But I’ve opted to stay out on the back deck, forcing myself to keep my eyes trained on the waves. I’m looking out for the seabirds of the Mediterranean—the large Cory’s Shearwater, which breeds in the Atlantic islands of Portugal and Spain, and the smaller Yelkouan Shearwater, which breeds on uninhabited islets and cliffs of the Aegean.

When I spot them all at once, a group of 14 or 15 Yelkouans and one Cory’s, gliding free along the sloping crests of waves, I feel like their flight encapsulates the magic of improvisation—to soar and glide. Musician Carlos Santana once described the best moments of improvisation to the younger guitarist Trey Anastasio as a moment of connection between the band and the audience, in which each musician is so locked into that specific moment, that "the music is the water, the audience is the flowers, and you are the hose."

The concept of hose in live improvisation is that rarest moment—the one-in-a-thousand moment of the most accomplished musicians, in the perfect venue, with the most attuned audience, where a moment just gels and something rare, unrepeatable and wonderful happens.

I feel like I can now imagine my quartet — I can see them. They have names, they have faces, and they are tuning to play in a Parian amphitheatre now.

Eula, fiddling with the reeds of her aulos, is originally from Athens, where she was trained on the aulos from an early age, like so many other children of that era.

Radamanqus, from Crete, unstrapping a custom-made kithara from his back.

Tullia, from the Italian peninsula of Salento, raised to write poetry and to sing, pulls out her various typanum drums and small percussion instruments.

And then there is Oumou, already noodling on the pandura. In my imagination, nobody knows where he was from originally, but it was somewhere west of Cairo. He made his way there as a young man, seeking a career as a musician. Every generation, the world produces someone like Oumou, who has a million musical ideas waiting to be played out. Having been born on the continent where call-and-response improvisation has thrived since the beginning of time, he always found an audience.

But maybe it was that night in Paros that he, with his pandura and his quartet, hosed the audience—a musical moment lost to time, like the flight of those seabirds, now vanished beyond the waves.