Europa

Liquid Architecture of the

Venetian Adriatic

In Venice, Istrian Croatia and Slovenia, I imagine the challenge of building cities as elegant as those of the Venetian Empire in tomorrow's world.

W

e begin our trip of the Venetian Adriatic in Venice, where I wonder: will there ever be another Venice?

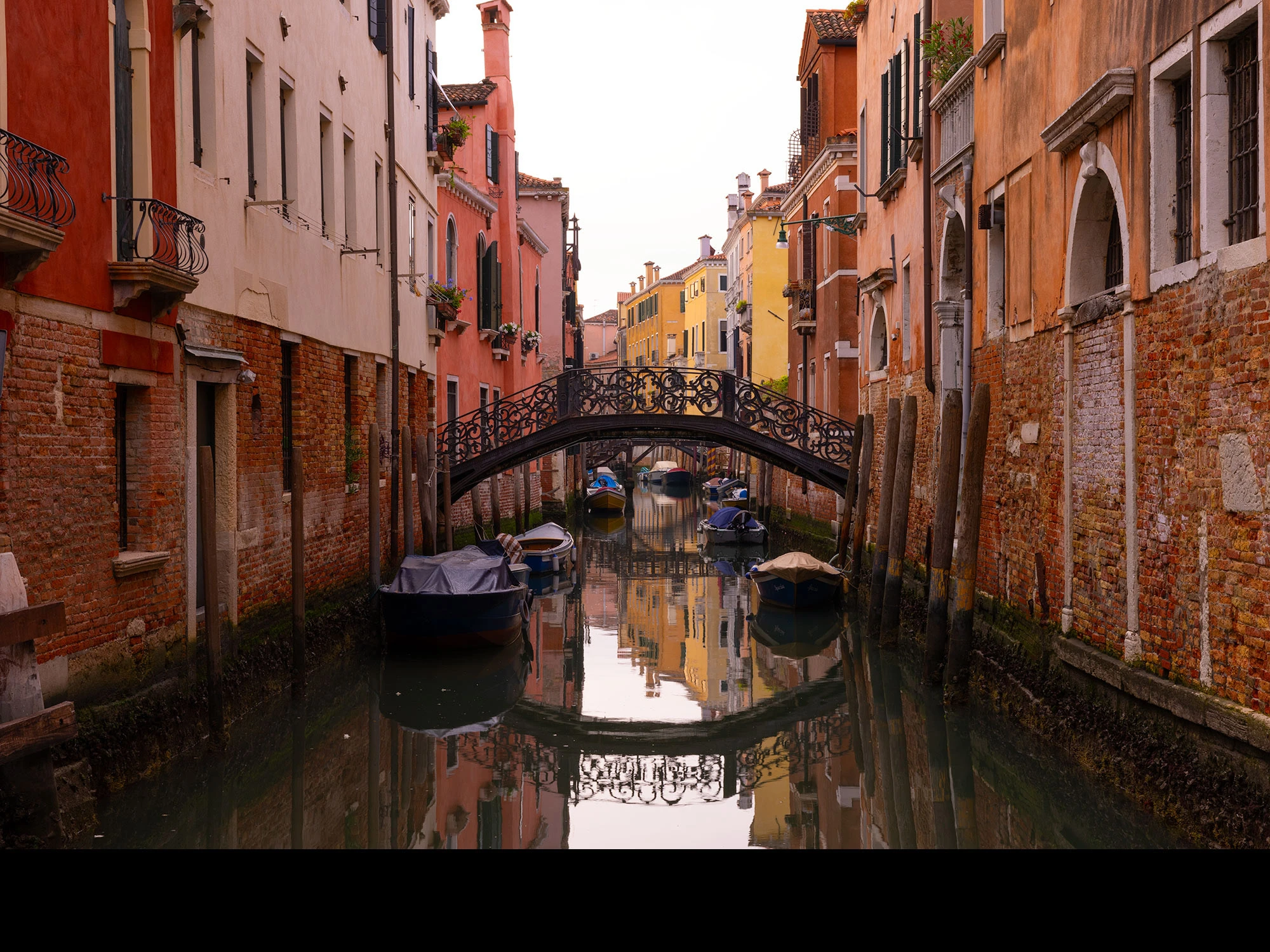

This city, we all know, is a globally renowned architectural dream. While some cities have well-preserved historic cores, none matches Venice's weird, unique unbroken cityscape. The completeness of its watery transportation, its arching bridges, intricate sculptures, and labyrinthine streets make it peerless. But I can’t help to wonder: will the future produce another uniquely elegant city?

On this trip, Jane gets what she wants most, to sleep in every morning. And I get what I want most. To get up at 4:30 and circumnavigate the city when it is completely quiet, completely still and completely absent of the throngs of sticky, sweaty tourists - spilling their gelato, pissing in the back alleys, hovering around foreign luxury shops.

In the very early morning, before the ruckus begins, you can see Venice the way it would have been seen two-hundred years ago. The city’s population is less than 55,000, and never was it denser than 100,000. While its economy began to convert into a tourism economy by the 18th century, it wasn’t until the 19th century that the city became entirely reliant on tourism. It was the time before this that Venice earned its beauty.

When I visited as a child in the 1980s, it was still a sleepy, quiet tourist city, populated with native Venetians out and about. I remember that time well simply because, as an American child who couldn’t bear to visit another church or museum, I was overwhelmed by the Venetian dreamworld—even a child gets Venice.

Humans on holiday are late-sleepers, and they are slow to start. This is a key to understanding and navigating so many places in travel. All you do is get a head start and you are back in 1983, or 1583, every alley you share only with the street sweepers.

A canal door in Venice features a pointed arch motif borrowed from Byzantine and Moorish architectural influences.

Edmondo Bacchi’s Challenge

T

he Peggy Guggenheim Collection, located on prime real estate of Venice’s Grand Canal, is featuring a retrospective of the 20th century modernist Venetian painter Edmondo Bacci. Through his sketches and paintings, the exhibit walks through his journey as a painter. Bacci’s earlier works are abstractions of Venice itself - timeless industrial architecture bathed in twilight light. But as Bacci evolved as a painter, you can see any hints of the real world dissolve, so that in the end, his paintings are just color and light; it’s like he is painting architecture, but without the buildings; more just an ethereal space; like some imaginary plane that is liquid and gas and air, expressed in a vivid ethereal palette. Just, as the Collection calls it, “the architecture of emptiness.”

Here we are, walking through the Collection, and something clicks for me. Bacci’s earlier work was inspired by his hyper-urban existence. But his later work lifted the wooden beams and stonework out, leaving a blank palette. Was Bacci telling the world that there was nothing stopping them from building the next Venice?

From the Ponte dell'Accademia bridge in Venice, Italy, you can see a blend of architectural styles. The most prominent are the classical Venetian Gothic buildings with their intricate facades, the elegant Baroque Church of Santa Maria della Salute, and Renaissance structures.

Early Days of the Venetian Lagoon

F

ourteen hundred years ago, the Venetian lagoon was an empty place to escape to. Like other northern Adriatic lagoons, It attracted people fleeing the huns or other forms of political persecution. To live in the middle of a saltwater marsh was to live in a place that could not be attacked and had nothing to offer. To live in Venice was to endure the tides and the mudflats for anonymity and safety.

There was no industry, save for salt panning and eel trapping. From 421 AD to about 850 AD, to live in Venice was to toil under the harsh sun in an isolated waterworld. The houses were simple; built of mud and clay, reeds and wood, wherever there might have been some hard-packed sand.

As population grew, the inhabitants needed to find new ways to make the shallow-water bay liveable. They drove wood pilings into the mud as a way to extend their real estate out beyond the hard-packed sand.

Venice was never master-planned. Its elegance was the result of the extreme environment, and the extreme lengths the Venetian empire needed to go to defend and enrich its citizens without having any substantial land to work off. Its system of government through the absolute rule of a doge was always transactional, never utopian, never artistic, never forward-thinking. Just hundreds of years of independence, the unique ability to repel would-be invaders, and unique relationships with Eastern and Western trading regions enriched the city. Venice had its share of luck, its share of naval military brutality, and an impeccable ability to use others to gain wealth. Money flowed down to the artisans and builders who slowly built up the impossible city.

It wasn’t until the 1580s that Venice started to deliberately curate the architectural styles of its past, as its elites saw themselves as preservationists of what they believed was the world’s most beautiful city.

These Venetian elites were lured by the Gothic architecture trends that had been taking Europe by storm for the past two centuries. But Venetian Gothic could never be like other European architecture. Being the center of Eastern Mediterranean trade, Venice was entranced by the art and architecture they knew from their role as a siphon between East and West—the decorative flourishes of the Byzantine Empire, and the Islamic motifs of the Moorish Mediterranean. The exoticism of pointed arches, ribbed vaulting, ogee arches, intricate stone tracery, and polychrome marble all come from these exotic influences that were ultimately absent from the rest of Europe.

After seeing the Bacci retrospective, we walk through a colonnaded overhang that trails alongside a quiet canal, and then turns ninety degrees through a tunnel and then over a bridge. This short space is a patchwork of exposed eras, all balancing on ancient wood pilings.

In the early morning, Venice is free of tourist traffic, and you can wander unimpeded.

Crossing the Adriatic

O

n a clear summer evening, we hop on the ferry to cross the Adriatic. It takes over forty-five minutes for the ferry to exit the Venetian lagoon, and this is the first time I can see that Venice’s architecture doesn’t actually end at the edge of the city. All of the populated islands in the lagoon share Venice’s architectural past.

Murano, with its charming squares, churches, and colorful houses. Burbank, with its pastel-hued houses lining its narrow canals. San Giorgio Maggiore, with its masterpiece, the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore. Giudecca, with its attractive palazzi along its waterfront promenade.

We follow the inner edge of Lido, the barrier island between the lagoon and the Adriatic, and all I see is a skyline as rich as Venice itself.

Out at sea, I am just looking for seabirds. I see none, which feels odd to me. But then I realize that the northern Adriatic is no deepwater oceanic fantasyland for wildlife. This is a sea dominated by the outflow of the Po delta—estuarine coasts, muddy saltwater, shallow seas, choppy winter water. When I look at eBird data for the middle of the northern Adriatic, I see only one entry, associated with a ferry route to Croatia. “No sightings for Year-round, All years.” A single bird has never been reported.

During the height of the Venetian Empire from the 13th to the 17th century, the Republic of Venice controlled a vast maritime empire that included territories across the Mediterranean Sea.

The Cannaregio neighborhood in Venice.

V

enice controlled large swaths of northeastern Italy, with cities like Padua, Verona, Vicenza, and Treviso, giving the Republic vital agricultural resources. They also controlled the islands of the Ionian Sea. Corfu, Kefalonia, and Zakynthos were strategically significant for trade and naval dominance in the Mediterranean.

Venice also had a presence in the Aegean Sea, particularly in the Cyclades islands. Naxos, Paros, and Tinos were among the islands under Venetian control. The republic established important trade routes and commercial outposts in this region. They even controlled Morea in the Peloponnese Peninsula in Greece. And, their empire extended to the large islands of Crete and Cyprus, giving them naval dominance in the Eastern Mediterranean.

But despite the breadth of its empire, the region that remained truly Venetian was the area we are passing through now: the north Adriatic coastline, the Gulf of Trieste, and the Istrian Peninsula—shared by Italy, Slovenia and Croatia—where the Venetian language persists in small towns, and many inhabitants see themselves as more Venetian than Italian, Croatian or Slovenian.

The enchanting coastal town of Rovinj in Istria, Croatia awakens to reveal its Venetian-influenced architecture, a reminder that another Venice is possible.

W

hen we dock in the Croatian port city of Rovinj, we are docking on what used to be a small mound of an island, which, under Venetian rule, developed the characteristic Venetian Gothic style of Venice itself. An old Venetian church spire rises from the center of the mound, and surrounding it, a miniature city as intricate and lovely as Venice spills out to its very edges; its homes and restaurants hanging out over the ocean. Smaller islands surround Rovinj; like in the Venetian lagoon, these too were built up.

Like Venice itself, Rovinj became an elegant and unique example of the completeness of Venetian architecture, an island city rising from the sea. Pointed arches, defensive fortifications, towers, lovely, bejeweled facades, and alleys that radiate out from the top of the mound—Venice with elevation.

While Rovinj is now connected to the mainland—in 1763 a plague scare forced the city to fill in the watery barrier between the island and the mainland as a means of escape for the island residents—for most of its history it was a self-contained island port, defensive outpost and a key to Venice’s control of the Adriatic.

Ancient cobbled street in Rovinj.

The Depiction of Sustainable Cities in Art and Illustration

A

rriving in Rovinj on a busy, bustling summer night, I am reminded of the question I asked myself in Venice. Here is a Venice in miniature. But if the Venetian Republic could duplicate their architectural masterpiece, could it happen again?

The case against this idea is a solid one. Venice had hundreds of years of unfathomable wealth pouring into its creation—a type of concentrated prosperity that may never be seen again. And Venice was built on a unique artist’s palette. Is there even an equivalent to the skilled artisans of the past? Where are the master stone masons and quarrymen who sculpted the intricate facades of Venetian palaces and churches? Where are the skilled woodworkers and carpenters, who carved lavish entryways and furnishings? Where are the glassblowers who produced intricate chandeliers, and the expert metalworkers and blacksmiths who forged iron piles and braces and gates?

But what if yesterday’s rules, and yesterday's skills, were not actually relevant to the creation of the Venice of tomorrow? What if the materials, the artistry, the economic conditions actually exist today?

This year, and particularly this summer, has seen the unprecedented advance of climate-fueled weather. In 2023, the climate disasters have spiked to levels that would have been impossible to imagine only ten years ago. Wildfires have destroyed entire cities, including the lovely historic capital of the Hawaiian Islands. Libya’s Derna Valley, once a paradise in its own right, saw catastrophic flooding that pushed nearly half of its namesake city into the ocean, killing thousands.

A sky blue door near the Church of St. Euphemia in Rovinj, Croatia.

T

he consequences of climate change are rising—and they are easily visible to everyone around the world.

To reverse the trends that would, if left unchecked, end human civilization, humans will have to make their cities green. Cities are the primary contributor to climate change, and are estimated to be responsible for seventy-five percent of all greenhouse gas emissions.

If humanity is to endure, it will need to retrofit, rebuild and rethink its cities. There are 10,000 cities with a population of over 50,000 around the world. Global treaties, trade laws, partnerships and pressure will almost certainly force most of these cities to change almost everything about them.

And sometimes, climate change and nature are giving cities a head start. Hawaii’s Lahaina, Libya’s Derna, and entire regions in cyclone-devastated Myanmar, are blank slates, waiting to be rebuilt.

Venetian Republic level capital outflow to green infrastructure is already happening globally. The U.S. Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, signed into law in the United States in 2021 is a 1.2 trillion dollar spend, theoretically anyway, on greener infrastructure throughout the country. The European Union’s Next Generation EU package is a bill that will spend 800 billion euros, about a third of which is slated to modernize the European infrastructure towards fighting climate change. Canada just committed to net zero carbon emissions by 2050, and China is currently spending $1.4 trillion towards green infrastructure. Perhaps most ambitious of all is South Korea’s Green New Deal, a direct investment of $55 billion into South Korea’s infrastructure shift towards net zero.

Grisia Street in Rovinj leads downhill towards the mainland section of the port town from the historic island center.

I

n the timeframe that Venice became the world’s architectural masterpiece, there were roughly 200 cities in the world. But in today’s world, bold investments in building green infrastructure are rising each year, and 10,000 cities await retrofits and reimaginings.

But what would a green city look like?

Graphic illustrations of green, sustainable cities almost always depict sanitized white buildings among unrealistically green foliage. Usually, the foliage is draped from the buildings themselves. Arced with sci-fi designs, the cityscape otherwise looks like a conventional city. People are out walking on eternally blue-sky days while sleek light rail trains zoom past.

These illustrations can be fun, and they often teach us some aspects of city life in a sustainable future. I know, because I’ve been a fan of the art trends that depict sustainable cities my entire adult life. Solarpunk, for example, is a successful artistic movement that explores sustainable futures—thousands of artists paint and write up fantastical futures with windmill landscapes and solar-plated cities.

But the sleek illustrations funded by grants and in green investment circles, and the sustainable futures depicted by the solarpunk movement are in no way accurate representation of how green, sustainable cities will look.

While illustrations of green sustainable cities serve as inspirational concepts, they often simplify the complex and multifaceted process of urban sustainability. Real-world cities always have very specific geographic contexts; and any greening city must navigate a multitude of challenges unique to their culture, their resources, their systems of economics and governance. Our cities of tomorrow will have more nuanced and varied approaches to sustainability than the common themes portrayed in these idealized images. Achieving net zero sustainability will be unlikely to produce solarpunk book covers—and it’s completely probable that sustainable cities will come in the form of artless refits of existing architecture —for the most part.

Rain begins to pour on the walled hilltop village of Motovun.

Traveling with Lana to Motovun

W

e wake to a sunny morning, hustling down through the cobbled streets, under gateways and arches, through streets that glow pink from colorfully painted walls, and down to a long esplanade to grab a coffee.

Hundreds of gulls and thousands of martins dart in the air above us, as if to queue up the day. We find Lana, a childhood friend of our friends back home, waiting for us in her van.

Lana was born near Stuttgart, not far from the town where my grandparents grew old, before moving to the Croatian part of Yugoslavia. “But, wait, you have to explain this to us,” I say, because I had never heard of a family willingly returning to a communist country.

“My dad’s friends and family said, ‘don’t come back’, but my parents, both Croatian, knew they would return home. Back then in the sixties and seventies, Croatians were looked down upon. Sure, Germany is different now, but back then, Yugoslavians and Italians were mistreated. The word in German is Auslander—alien. Germany was a great place to live, but it was not home to my parents.”

“I grew up speaking both German and Croatian, but on the day it was time to leave Germany, when I was ten years old, and on the drive south to Croatia, it’s like I could no longer speak German. Something inside me was telling me it was time to be Croatian. But when I arrived in Croatia, I learned that the kids were rough to each other, but really rough to me. They called me the German girl, and didn’t accept me. I was crying every day, and for me it was a very difficult time, but I remained adamant that I was a Croatian.”

A typical wooden Istrian window in Motovun, Croatia.

J

ane asks Lana what else was different about moving to Yugoslavia.

“Well, there were other parts about being in Yugoslavia that were difficult. Christmas is a big deal in Germany, and that was my favorite day. If I could, I would celebrate Christmas 365 days of the year. But in Yugoslavia, there is no Christmas. You actually go to school on Christmas day. That was so difficult for me. And of course, there was no chocolate in Yugoslavia! And no detergent!”

As we leave Rovinj, the outskirts of the city quickly dissolve to green. There are vineyards and olive groves and little villages, but also big swaths of wild forest. There are hills and cliffs and turquoise rivers.

And then, we round a bend and there it is, Motovun, a divine medieval town built at the crest of a steep hill. Lana loves this Istrian countryside—its wines and olives and truffles—but I can sense that this view still gets her. Motovun, which under Venetian rule acquired its city walls and terracotta-roof skyline, is another pint-size Venice, a beauty built on an impossible canvas.

There is one key difference between the beauty of Venice, and the beauty of both Rovinj and Motovun. Venice is so completely built up that there is, quite obviously, scant vegetation. There are trees in Venice, of course, and even a large curated garden with magnificent trees. But the natural landscape and vegetation has a much bigger role to play in these Croatian Venices. Seeing how Motovun blends into the native landscape makes me want to imagine what Venice would look like if native vegetation was integrated back into the city and lagoon.

While walking up into the hilltop town, Lana explains how these were the streets where Aldo and Mario Andretti, born here, raced each other on the continuous downhill cobblestone of Motovun.

Pre-dawn on Vladimira Švalbe street in Rovinj.

The Building Blocks of a Sustainable City

S

o if there is to be another Venice, we need to define what these retrofits and rebuilds will be made of.

Cities are our primary agents of climate change largely because of industrial and motorized transport systems that use huge quantities of fossil fuels and rely on far-flung infrastructure constructed with carbon-intensive materials.

We already know the basic building blocks that would make cities net-zero, or, cities that convert towards a balance between the amount of greenhouse gas produced and removed from the atmosphere.

Such a net zero city would have buildings that have been completely electrified, and all transportation would be either electric or mechanical. The energy sources for this electrification would be completely renewable, and non-renewable energy, like natural gas, diesel, oil and gasoline, would be forbidden.

Such a city would be walkable, with foot or manual transportation a key to its design. Food would be renewable, and much of the food would be derived locally, from urban, suburban and exurban agricultural sources.

The city would have air as clean as the nearby forest. Real rivers, real streams, and native vegetation would thrive everywhere.

Housing would be dense and vertical, and buildings would be lush with trees, vines and shrubs; living walls. Rooftops would be gardens and farms or just green with life, and there would be vertical farms everywhere. Even bays and canals would feature vertical farms, with sustainable clams and mussels growing along ropes in the deep channels.

Everywhere, there is space for wildlife, and native vegetation thrives. Butterflies, native salamanders, birds and small mammals are abundant. The air smells like the forest.

Composting is part of everyday life, and zero waste is a way of life. Homes and offices are built with HVAC systems that largely rely on passive solar building designs.

These building blocks to net zero may sound impossible, or utopian, but the marketplace is already innovating the buildings of the future, the building materials of the future, the transportation of the future and the paths towards efficient electrification. Many cities around the world are on successful paths to achieving carbon neutrality. Some are requiring all new constructions to be entirely electric. Some, like Los Angeles, are ending any oil production in their city limits. New architectural wonders, like Portland’s Carbon12, is a 12 story wood building, built with cross-laminated timber. The building is considered one of the most climate-friendly in the world, and a pioneer of tomorrow’s sustainable building techniques.

Arched tunnel and traditional door in Rovinj, Croatia.

Piran and the Sečovlje Salt Pans

T

he next morning, we meet Jakov, Lana’s husband, and cross the border into Slovenia. We walk around the Sečovlje Salt Pans, a hybrid area of Roman-era salt pans and the wildlife-rich Sečovlje Salina Nature Park.

The Sečovlje flats, formed by the Dragon River delta, are among the last traditional, manual pans in the Mediterranean; the light footprint of the salt collection is a reminder of how humans can extract food while coexisting with wildlife.

We are dragging Jakov to look for European Bee Eaters, among the most colorful birds in the world.

The massive estuary features long, raised footpaths which are dotted with dozens of old, abandoned stone homes. Lana had explained that the owners of these homes had ripped their roofs off to discourage anybody from inhabiting them, when they fled Slovenia for Italy at the onset of the Yugoslav state. But they never returned, and now these ghost houses haunt the backwater parts of the estuary.

As we drive the short distance from the salt flats to the Slovenian city of Piran, we catch glimpses of a large portion of the country’s 29 mile coastline. Despite its small size, the Adriatic portion of the country features some of the most stunning coastal cityscapes in the Adriatic, and Piran is among its Venetian jewels. Like Rovinj and Motovun, Piran is a Venice in miniature: narrow, winding cobblestone streets, colorful renaissance buildings, an impossible compact layout, taking up the whole of a long Peninsula, jutting out into the sea. The Venetian influence can be seen in the design of many buildings, with their ornate facades, arched windows, and red-tiled roofs.

An abandoned pre-Yugoslavian salter house in the Sečovlje Salt Pans in Slovenia.

O

ne of the things that makes Piran such a lovely place is that the city is too compact for cars, forcing the city to regulate the entry of vehicles carefully. This makes for a very vertical city, where you can get anywhere within five minutes.

In Piran, I can’t help but think about the concept of the "fifteen-minute city", the idea that cities of the future can be more livable, environmentally friendly, and efficient by redesigning urban spaces to ensure that people can access most of their daily needs within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from their homes.

The allure of a 15-minute city is especially tantalizing to us Americans, who managed to give up our old main street towns for endless, unwalkable Suburbia - a national architecture built for cars, not people, where we have to drive just to walk.

But, what will that 15-minute city actually look like - the one that is as elegant as Venice, but built with the building materials of tomorrow?

Like Venice itself, geography is going to dictate that. A green city in North Africa is going to look very different, and use completely different construction materials, than a green city in Siberia, or Brazil, or Oceania. The one thing I know is that humans, when given the chance, rise to great aesthetic challenges.

I try to take everything I know about sustainable cities, and the beauty of the liquid architecture of these Venetian masterpieces, and then I overlay that in a daydream to the human desire to build and live for more than just economy or convenience.

At this crossroads, will we retrofit our cities just to survive? Or will we compete with each other, yearn for greatness, imagine and build, and go all the way.

I cycle through cities in my head. Jane knows that when one of us can’t sleep, I’ll tell stories in imaginary landscapes to coax ourselves asleep. But today, I am drifting away from Piran while daydreaming along the harbor’s edge, watching the minnows dart between boats.

The harbor in Piran, Slovenia.

W

e are somewhere in the world that is arid. Somewhere completely different than Venice. It could be Spain or Morocco or California.

Buildings rise twenty, thirty stories in the air. They look completely different from what we know as buildings today. They look organic and are colored pottery red or gamboge, with round shapes and arched windows and long, wide bridges that cross from building to building, like adobe skyways. This construction material, designed to eliminate greenhouse gasses in its creation, and sequester carbon, is bio-based—plant material—some near future concoction of wood, clay and straw that outdoes steel and concrete on strength, durability and fire-resistance, and, in this city anyways, effectively ends one of the primary instigators of greenhouse gasses.

Native palms and chaparral seem to grow on every flat surface. There are no exotic hibiscus or bright green maples. Every plant and tree and shrub and bush comes from here. To someone in our era, completely native plantings may look like dull choices, without the flamboyant exotics colors of elsewhere. But the simple blue-ish and olive hues common in arid environments complements these buildings, this land, this place.

From an adobe skyway you can look down and see one of several creeks meandering through the city. There is a footpath down there but most people move about from building to building at elevation. There are roads too, but electric cars and trucks are mostly used for commercial and industrial transport, as you can get anywhere you need to go by foot.

The vehicles, mostly, are bicycles, and the skyway streets are large enough for the pedal-power quadricycles, transporting grandmother to the art gallery. Like the gondolas of Venice, there are strict requirements on how these quadricycles are to look and function. Only three colors of canvas—tangerine orange, camelbak or opaline— can be stretched across their hoods, and those distinctive wheel wells must be hard-carved from the native cypress groves to the north.

These tall adobe-like structures with their thick walls, small windows and elevated verandahs are built with solar designs. They stay cool in the summer, they stay pleasantly warm through the winter. In a way, they are like a thousand Great Mosques of Djenné, but the modern building materials allow these structures to soar —-and maybe I forgot to tell you, but the material generates electricity. Its outer shell is embedded with a material like a Tesla roof—invisible solar panels.

Gnats rise up from the creek ecosystem below in the millions. Without the noise of gas-powered cars, the only sound is the rustle of leaves and human voices and the swallows chittering as they dive bomb the clouds of insects.

This is not a Utopia. It is a well-designed city. It has problems; the rusty skeleton of the pre-retrofits are evident everywhere. There is litter and graffiti and crime. But the city is liveable, walkable and functions as a net zero city. It has its problems. All this new technology doesn’t work perfectly. Things fall apart, and in some cases, a newer and better invention comes along, skewering somebody’s decision to use yesterday’s solution.

Venice—whose wood and straw-roof construction made it a constant victim of massive city fires—found itself in a position of having to retrofit and reinvent itself—and sometimes, those fires allowed the city elites to rebuild something even better than what was lost.

Most cities won’t be as singular as this one—wherever it is—but math works out in our favor. If we commit to net zero cities, as many around the world already our, there will be more than one Venice in tomorrow’s world.