West Indies

Cuba Sketch Journal

Sketches and notes from Cuba, drawn in Moleskine with liner pens, watercolors, and Copic markers.

Sketching the Havana Cathedral

When you look up close at the exterior of the Havana Cathedral, you can see the shapes of brain coral, seashells and ancient marine fossils. The cathedral was built from coral bedrock, carved out of the nearby bay, a reminder that while some aspects of this baroque Jesuit cathedral borrow from the old world, these famed Havana buildings are firmly rooted in the West Indies.

Havana Cathedral, or in full, The Cathedral of the Virgin Mary of the Immaculate Conception

Seeing these old buildings in Havana was my reminder about the way we talk about Cuba in the United States, which is this very black-and-white way. To see each of these old buildings is to give a timeline to Cuban history. Even if that architectural timeline is surface-level, it kept tugging on me, reminding me that the opposing storylines we’re fed in the United States about Cuba are incomplete, making them deceptive. I began to wonder if America’s Cuba story actually intensified the island’s sad recent history, and I began to listen more closely to the way different people talked about Cuba.

When Castro died, I had already had my ticket to Cuba for over a year, and the reservations department at Delta graciously let me keep pushing my flight back through a whirlwind of political events, hurricanes and even a tweaked lower back. During all this time, I listened to the conversation about Cuba.

Finding historically accurate depictions of Cuba is missing in American dialogue, and this became especially true as almost every American conversation settles on Fidel Castro, as if this 17th largest island in the world was populated by a single cigar-smoking dictator.

On the day of Castro’s death, an article by Humberto Fontova, a Cuban-American exile who has made a career writing about Cuba, sought to paint a grim picture of Castro. “He murdered more Cubans in his first three years in power than Hitler murdered Germans during his first six,” Fontova begins.

The Gran Teatro de la Habana

The Gran Teatro de la Habana, completed in 1915 by Galician immigrants, was reopened in 2016 and hosts opera and concert performances by Cuban and international artists.

I thought this was a strange comparison, because while Hitler imprisoned political prisoners and began building concentration camps in his very first year of power, murdering his own citizens had not yet begun.

Fontova’s rhetoric was unnecessary in its exaggerated wordplay. Like Hitler and countless numbers of despotic dictators, Castro’s list of atrocities is repugnant and unforgivable. But in his article, Fontova chose wordplay to embellish Castro’s record without really explaining what Castro’s atrocities were. Why?

His sharp turn explains the reason. He says, “Would anyone guess any of the above from reading or listening to the mainstream media recently?”

After painting a picture of Castro as the equal of Stalin and ISIS, Fontova quickly turns to America’s media and it’s politicians, painting them as ignorant and forgiving of Castro. He strings together a series of quotes from U.S. television anchors and Hollywood celebrities, which has the intended effect of making it sound as if much of America, especially its media, Hollywood and political elites, are willing accomplices to a Caribbean Pol Pot.

Exotic tree at the Jardin Botanico Nacional near Havana, Cuba.

For example, Fontova quotes news anchor Dan Rather; “Fidel Castro could have been Cuba’s Elvis,” intending the phrase as a way to prove that yet another in the U.S. media have fallen head over heels for Castro, ignoring his record.

But like all his quotes, Fontova is misleading us with quotes isolated from their context, because Dan Rather, throughout his career, made the important point that Castro was charismatic, even if his policies were despicable.

Footage of Castro supports this. In the recent Netflix documentary, “Cuba and the Cameraman,” which holds a one-hundred percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, an American filmmaker’s 45 years of filming Cuba are edited down to a single feature-film length documentary.

In this documentary, documentarian Jon Alpert spends countless years revisiting the country, and succeeds in befriending various families throughout the country. He also succeeds in conducting interviews with Castro throughout those forty-five years.

Throughout the footage, you can sense how Alpert’s non-aggressive approach, and his friendly manner toward Castro, earn him repeated visits. Fontova would argue that Alpert’s documentary is just another example of the media and Hollywood gushing praise on its dictator.

Fortifications in Havana

Fortifications line Havana Bay along the Malecon.

The opposite is true, because Alpert manages to show, in human stories, the undeniable destruction of Castro's Cuba at street level, while also managing to film its leader. The result is the opposite of Fontova's deceptive journalism: a view of Cuba, told from its own people, and presented as more complex than Fontova's narrative. There is no way for anyone to walk away from the film and not understand that it’s leader had charisma, while at the same contributing to driving it to tatters.

Even if Alpert unleashed forty-five years of softball questions on Cuba and its leader, he brought back footage that was real. The footage didn’t tell us what to think, but it gave a rare window into a world that was almost a complete black hole to American journalism for half a century.

It is in this black hole that people with an agenda, like Fontova, have been able to come in and offer up a Cuba and Castro as a political statement, a Cuba spun from wordplay into black and white.

Cocotaxis, or Coconut Taxis, are common in Havana and other large Cuban cities.

It turns out that Fontova is a regular with Sean Hannity and Bill O’Reilly, and his books are sold to the sort of vapid right-wingers who eat up Ann Coulter and Milo Yiannopoulos.

Now his immediate turn from Castro to the U.S. Media makes sense, because Fontova uses Cuba for the same goal and theme that is the common one to all of America’s extreme right-wing media; the selling of the need for an alternative to the mainstream media.

There is also a common political theme among this group in America: Cuba is a communist country, Castro is evil, therefore continue to isolate Cuba.

I grew up always knowing this was backward thinking. I tasted Cuba through its exile workers in the Bahamas growing up. Those brief childhood conversations were enough, for me, to see a street-level view of the effect of Castro’s communism. But these real people were also a reminder that there was more to Cuba than fatigues and red stars.

Cuba was a country whose fall into dictactorial communism was the result of more than Castro alone. I like to think of it more this way: Castro was the inevitable result of the U.S. puppet administration that preceded him, which was just as brutal, and which actually murdered more people per year than the Castro Administration, and Castro was the result of the war games played by the superpowers in the Cold War.

Cuba and the Wargames of the Superpowers

While we know the story of the antique American cars of Cuba, I was taken by the fact that the British, Italian, Chinese and Russian antiques also abound. One of the most stunning was this well-preserved four-wheel drive vehicle from China.

Because the U.S. had a hand in building a pendulum that swung far one way, Castro was just the weight of the pendulum then dropping the other. If the United States had created many of the conditions that created Castro, why have we worked so hard to isolate Cuba for fifty years; an economic blockade that perhaps equals the role of Castro’s communism in keeping the country in a state of perpetual despair?

While Castro was a despot, the Cuban government grew increasingly benign over time; it’s bureacracy was more than it’s famous leader. It’s economic system stank, but there were also bright spots worthy of attention. In it’s darkest moments, isolated even from it’s communist allies, Cuba made notable advances in healthcare, literacy, education and the arts.

In its darkest times, Cubans became examplars of a unique ingenuity and ability to persist, thrive, and even feed themselves.

The Lonja del Comercio building was Cuba's stock exchange up until the 1959 revolution.

The United States’ economic blockade of Cuba has been outdated for at least thirty-years. Is it really U.S. policy to blockade countries whose governments humanitarian records are subpar? The governments of some of our closest allies had much worse records than the Castro regime. Consider our relationship with Saudi Arabia, or our post-World War II forgiveness of Hirohito.

But Cuba is different from Japan and Saudi Arabia; Cuba, at the start of the twentieth century, was the country that most resembled the United State. Its people looked up to mine, imitated it, borrowed from it, made it their own. While the rest of the West Indies draws its cultural center from elsewhere, the Cuban people always first looked north.

So why then, do we continue to isolate Cuba, when their people, in our own backyard, were punished by our own puppet regimes and Cold War games? If we forgive other government’s, what is it about Cuba?

In a 2014 editorial in The Economist, the paper argues that the United States has, "failed to dislodge the Castro regime of either Fidel or, since 2006, his brother Raúl. Indeed, by enabling the island's rulers to present themselves as the victims of hegemonic bullying, it has shored up support for Cuba abroad and given an excuse for totalitarianism at home. America's allies think the embargo is counter-productive at best, vindictive at worst."

Foreign policy experts have been sounding this same call for years; economic embargos and the isolation of Cuba harm the people, unnecesarily create a global hero out of Castro, and slow its plodding path away from communism.

The Chinese Government in Cuba and the West Indies

Among the fine examples of architecture in Havana are the many shabby Soviet-era buildings, which make parts of Havana resemble an earlier Poland or East Germany.

When I go birding in the Bahamas, and head out on the long, quiet roads of the Abacos, sometimes I will come across something that strikes me as almost alarming. A huge structure, fenced off and being erected in the middle of nowhere. Who is building it? Why is it here? It’s a port, it’s a power plant. It’s being built by a branch of the Chinese Government.

Really? Ninety miles from Miami, the Chinese are building ports and power plants?

When we isolate a region, or ignore it, we create an opportunity for others to make inroads. China has been making deals and inroads with the Bahamas for years; but their presence is exploding throughout the Caribbean, and nowhere is that presence more obvious than Cuba itself.

Does it make sense for China to be economic patriarch to Cuba? Is it in the best interest of our role as an economic force in the Americas?

When Fontova and Fox News press the case for a continued blockade of Cuba, what do they achieve? A win for the purity of their political views. But a better argument is that the blockade itself has prolonged Cuba’s communist era, and perhaps even prolonged the life of the Castro regime itself. The Castro Administration’s communism may have been necessary to lure in its various Communist sugar daddies, from the Soviet Union, to China, to Venezuela.

Now, we’re months away from the end of the Castro hold on power altogether. Continued blockades will encourage the new leader to find economic partnerships elsewhere. And that will partially explain why China just spent seven-hundred million on infrastructure projects in Jamaica, and major Chinese investment projects popping up down the spine of the Caribbean archipelago.

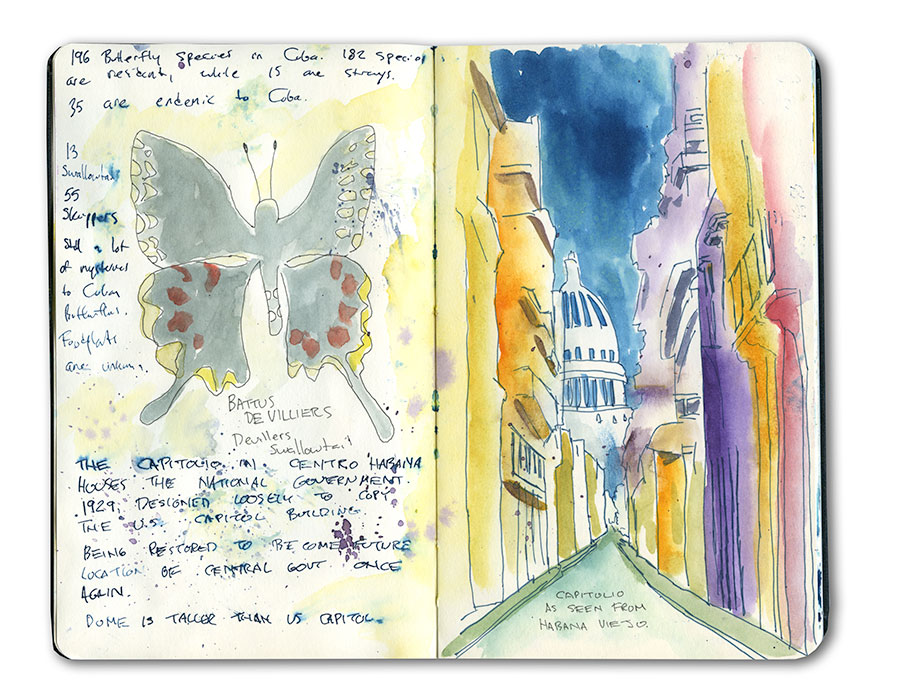

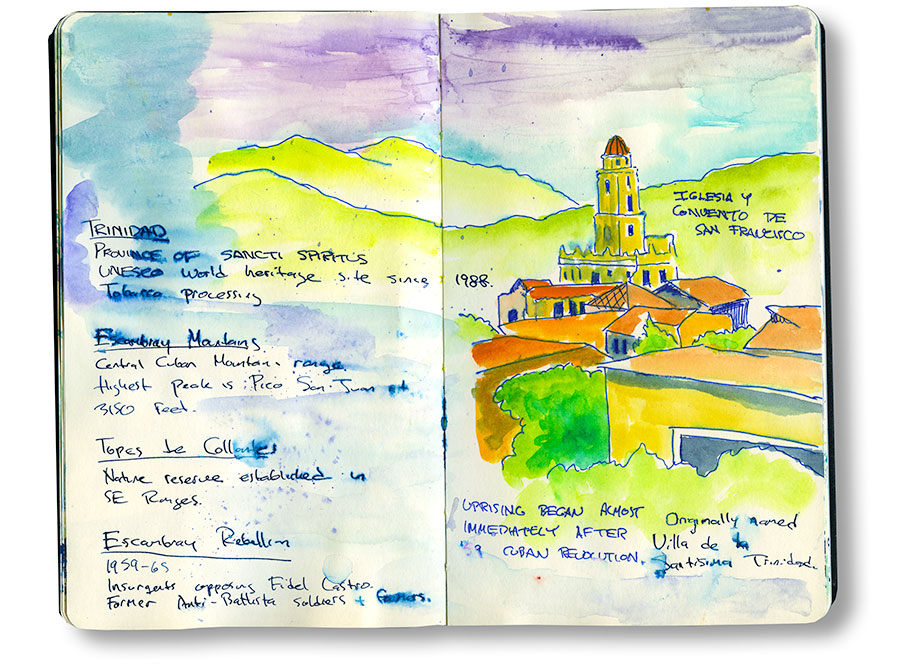

Cuba Moleskine Journal

Below are my Cuba moleskine sketches and notes, which I used as an early draft of my Habana Vieja and Sancti Spiritus notes, about my quest to find a small bird, endemic to the island of Cuba. I used different mediums in this journal, including Noodler's ink and nib pens, watercolors and Micron liner pens.