Cascadia

The Ark Saucer

of Sauvie Island

On a quiet stretch of Columbia River beach, an unexpected ark sends us to discover the life of the maverick inventor who built Sauvie Island's UFO boat.

Above: The Columbia River, as seen from Broughton Beach near Portland International Airport during a typically drizzly winter morning.

I

t was just meant to be a regular walk along the Columbia River beaches of Oregon’s Sauvie Island on a cool, gray winter morning. Who knew that we would stumble upon a multicolored, saucer-shaped ark, and that it would lead us toward the life of genius inventor Richard Ensign.

In the winter months, Sauvie Island, the massive river island which lies just northwest of Portland and Vancouver, is barren and lonely, and its agricultural fields are all flood and mud. I notice something bright blue set back behind the beach.

Portland’s housing crisis has meant a swell of hidden encampments in places where most people never care to look; and after surprising enough wary homesteaders, I’ve become more cautious. Just the sight of the color blue—tarp shelter.

Signs on this isolated beach remind us: Collins Beach is clothing-optional. It’s just warmer than freezing, the sky is damp. We are the only ones here, I think.

Still, I am cautious about that structure up ahead. Through the binoculars, I change my opinion. “It’s not a shelter. It’s a vehicle?”

Kellan, my eleven year old son, now sees that as well, and he runs ahead, holding his video camera as he approaches.

My wife and I follow, walking along installations of handmade mobiles and windchimes, hung alongside the Columbia River in past seasons from sun weathered driftwood branches.

When we arrive at the edge of the beach and woods, there it is, this monstrous vehicle, graffitied in brilliant paint. Kellan announces: it’s some sort of boat. He thinks it’s not made of fiberglass. Or wood. Some kind of stone. Maybe concrete, papa?

But as we gawk over the intricate graffiti, Kellan is live on the mic. “It is shaped like a flying saucer!” He is trying to get inside the round-portholed trimaran.

I climb up a carefully placed log to the ship’s deck, and looking inside, I see Kellan’s shadowy figure, speaking to his Youtube audience. Why it is here, I do not know. What it is doing on this beach, I have no idea.

When his video session ends, I enter. “What do you think this is?” he asks. “Why don’t we try to find out more about it?” I reply. Somehow, I don’t need to say it. He’s been bitten by a bug to document our find, a story that is just his own.

Sunweathered mobiles at the clothing-optional Collins Beach on northern Sauvie Island. Oregon's coastal range is in the distance, and a non-accessible region of Washington State's Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge is across the river.

Finding Richard Ensign

I

n 1973, the boat was hoisted onto dollies, and towed by truck; power lines were raised to allow the massive boat to be carried from the corner of G Street and Whiskey Hill Road in Hubbard, to a dock on the Willamette River. Traffic stopped and everybody stared; the Associated Press dubbed it the Floating Saucer, and an unlikely concrete boat slipped into the water. With a crew of 8, but room for 12, the two-sailed trimaran began a voyage to prove Richard Ensign’s mission: that ordinary people, working together, can themselves slip free from the repressive clutches of society, and find freedom and liberty on the open water.

Back home, Kellan feels unsatisfied by the online stories about the boat and its creator, civil engineer Richard Ensign. And so do I. Who was this engineer who built this concrete saucer-shaped boat, and why?

Two months later, I am at the Loyal Legion bar in southeast Portland, meeting up with one of Richard Ensign’s six children, Jon.

Over a beer, he says, “We had this modest life, but we never lacked anything. I felt like I had everything. Dad taught us to learn how to be resourceful. If there was a disaster right now, if there was an earthquake, I think I would not only survive, but thrive, and be able to help others.

Dad could not let anything go to waste and it pained him to see perfectly good produce being tossed by supermarkets and fields in the Willamette Valley not picked clean. He taught us that we shouldn’t waste food or resources. Bruised fruit could be the most sweet and not letting it go to waste proves our humility and that we are no better than anybody else on this earth, from the poorest of the poor to the wealthiest, and to anyone in between.”

I ask him about his dad’s schooling.

“Upon enlistment, the navy sent him directly to Princeton University as part of a World War II officer training program, and then Columbia and the University of Michigan. He told us about meeting Albert Einstein who lived at Princeton. But despite all this education, he had his own way of communicating that discouraged questioning and judging others and use of definitive words and phrases. He didn’t want to be perceived as an authority and tell others what to do. What he taught us as kids was rely less on questions to others and more on personal observation, experiential learning, attention to response and then share what you’ve gained if it can help others.

As kids we’d phrase things like 'Possibly, maybe we can go over and see my friends.’ His reply would be something like 'Do as you are impressed or as the spirit leads you.'"

I ask if he worked for state government.

“Early on he worked for the Army Corp of Engineers. He was a civil engineer and when we were young he worked for a couple small engineering firms. He discovered engineering problems with the Fremont Bridge and worked on electrical grid structure. He was drawn to concrete about the same time as he was doing the work on the Fremont Bridge in Portland, and if you look at that bridge, you’ll see that the curvature in the supports are similar to those of the boat.”

Ice patterns found on frozen leaves on Sauvie Island. The island known as one of the largest river islands in the United States, is also the largest island on the entire length of the Columbia River.

W

e start to talk about their early years, and his dad’s evolution from civil engineer towards a singular focus on the boat.

“At this time, dad was into taking the most mundane of things and putting them to work for him. Rather than buy a cement mixer, why not take a lawnmower engine and a fifty-gallon steel drum and make your own.”

“On a visit to Seattle, we visited Pike’s Place Market. There was this group from the Caribbean playing drums made out used fifty-gallon steel barrels. Dad was quite impressed at this idea that you could make this beautiful music out of something he’d used so often in other ways.

When we got home, he made soft rubber mallets of different sizes and had us kids see what sounds would come out of drumming on the car. We were so embarrassed at the idea of this, so we drove out to a cemetery, and we were playing music on our car where no living person would hear us. He saw a performance as a possible way to reach people and share some of his insights and solutions for an increasingly divided society.”

“Concrete has become so popular in modern design,” I say.

“That was back in the early seventies, when dad really started experimenting with concrete. And now floating cities are being built of concrete and foam!"

I ask him about the time that work on the boat began—when his dad began to drop out of normal society and remained largely absent as a provider to the family.

“As a child, we gave up our back yard in Hubbard, Oregon for the boat construction which eventually towered over our home. Our home, by the way, he had designed and built in panels with a flat roof modern construction and assembled it in a day. Our home, like the boat, was an experiment as an opportunity for people to afford a home of their own that they could build themselves. Over the years I have seen similar designs and construction methods come about and gain interest. The boat was dad, and dad was the boat. He was actively working on the boat project on the water in Washington from 1973 to 1983; over ten years, and then continued new prototypes that would be easier for others to build through the 1990s. It was the thing that would define him. He felt a calling.”

To build the boat, Richard Ensign first designed and built the equipment he would need, such as a cement mixer made from a 50-gallon steel drum and an old lawn mower. As a child, Richard’s children each had jobs in the construction of the build. For example, Jon’s job, at age five, was to cut metal wire to two inch pieces and bend them into U shapes, while the older brothers would take those pieces and secure the metal mesh to the rebar of the boat’s frame.

“My eldest brother and a friend of dad’s did the heavier work. When it came time to cement the boat hull we all had our gloves on to push the concrete into the metal mesh framework before it was then sprayed with foam on the inside.”

In an intense winter fog, dense dew drops form on the webs of funnel spiders.

Taking to the Tidelands

I

explain that, like my son, I didn’t feel any of the material out there was explaining why his dad had built the boat.

“He felt a calling to design methods of construction that anyone could do, that anyone could afford and use to go float away to live a life of their choosing. He saw too many restrictions on personal liberty by city and county bureaucracy and codes and believed that people could take to the sea or, specifically the tidelands in particular, and to live as they desired.

One day, we were in a concrete rowboat that dad had built. It was low tide, and there was this giant school of fish along the shore. We jumped in the water and grabbed the net.

At the time, I was wondering why these fish were so close to shore. Why were they trying to get out of the water? At the time, I didn’t realize that this was a fish jubilee; a rare event where oxygen is so depleted in the water that it forces the fish, and everything else in the water, to come to shore.

But dad was teaching us something; that you can live out there in the tidelands, catch fish, build a smoker out of corrugated metal and fire it with alder branches and leaves.

Tell me about spending time on the boat yourself as a kid? I ask.

During the day, we’d climb on and around the boat, explore the mossy forest, fish and even fish inside the boat. We’d move the table top and drop our line right through the concrete table base. Dad was always thinking about new ways to use space, to re-adapt everything to new purposes. My strongest memory is being in a one of the bunks with a curved wall and portal window, the gentle rocking on the water, going up and down with the tide; a fire burning and looking out to the logjams across Deep River, Paul Harvey on AM radio, a waffley and foggy sound through our quiet time.

Years later, I was in remote Levuka, Fiji at the old Royal Hotel. The elderly woman owner, who’s parent had built the hotel, had a radio playing and that waffley sound carried through the air instantly brought me back to those days on the boat.”

Richard Ensigns 1973 trimaran-hull boat was built with steel and concrete. It featured two sails, a center table that could be converted into fishing hole and fireplace, and room for a crew of 12. The boat was also self-righting and designed to weather extreme tidelands conditions.

The Circular Ark of Babylon

I

tell my brother about my interview about the boat, and he immediately retorts: “Oh, that’s the ark story.” When he says that, I recall the story of Noah in the Book of Genesis:

I am going to bring floodwaters on the earth to destroy all life under the heavens, every creature that has the breath of life in it. Everything on earth will perish. But I will establish my covenant with you, and you will enter the ark--you and your sons and your wife and your sons' wives with you.

But my brother had recalled a Nova episode about a recent discovery of a Babylonian cuneiform tablet, which described in detail how to build an ark, and thus provided historiographic insights into the Biblical story of Noah’s Ark.

Catastrophic flooding was commonplace in the Babylonian era, particularly between the Tigris and the Euphrates, where stories from centuries of floods had built up both myth and a universal desire to survive a very real threat.

The Babylonian version of the ark story, which shares the same fundamentals as the Bible’s ark flood story, gives specific instructions on how to build a circular ark.

Pay heed to my advice.

That you may live forever!

Destroy your house, build a boat!

Spurn property and save life!

Draw out the boat that you will make

On a circular plan.

Let her length and breadth be equal,

Let her flood area be one field, let her height be one nindan high.

My brother was right: The earliest description of ancient arks described a circular craft. Not something that you sail, per se, but something that sits in your backyard or your town square, ready to float away from catastrophe. But the next part of the description, describing how the boat is built of bitumen, a natural asphalt, blew me away:

I apportioned one finger of bitumen for her outsides;

I apportioned one finger of bitumen for her interior;

I had poured out one finger of bitumen onto her cabins;

I caused the kilns to be loaded with 28,800 sūtu of kupru-bitumen

And I poured 3,600 sūtu of bitumen within.

I added five fingers of lard,

I ordered the kilns to be loaded in equal measure.

When the Nova team set out to rebuild a round ark as described in the Babylonian scripts, it looked amazingly similar to Richard Ensign’s concrete trimaran saucer, even though the evidence of circular arks was nonexistent during his lifetime. Was Richard Ensign building an ark?

Oregon's rich aquatic wetlands are reflected in these spiderweb dewdrops. It was in this environment that the Multnomah Indian bands foraged for wapato and built up a community of 15 villages on Sauvie Island.

The Willamette Valley Flood

J

on explains that years after the initial boat-build, He began to develop floating homes that could float in six inches of water and rest on mudflats at low tide.

“On one of my visits home from Japan, Dad took me out to his project on the Willamette River to show me a prototype home and trailer that would be backed into the water, the car then driving up on the trailer and providing the motor and steering to dock the car and trailer into the floating home and drive the home as a boat. This home style was based more on a very simple panel construction that anyone could do as opposed to the more complex trimaran engineering of his first boat-home.”

Richard Ensign sold the boat as well as a larger, later model, in the early 1980s. Under new ownership, one may now sit at the bottom of the Columbia, and the original boat was destined to its final Sauvie Island resting place by the Great Willamette Flood of 1996, an unusual and devastating climate event which left three-thousand displaced, eight dead and half a billion dollars in damages across the West. The flood pulled the boat from its moorage far above the usual high-water mark, where it remained largely hidden in the woods, and a mystery to locals for the next fifteen years.

Was he building a boat, so that like-minded survivors could escape a political, societal or even environmental apocalypse?

The interior of the boat, including the center table area.

B

ack at home, I open a box of letters that Jon lent me, and share them with my own son. Though he’d experimented with ink from Oregon Grape berries, these letters were penned in ink, on the thin, fragile paper of restaurant napkins. His cursive is beautiful, but, faded by time, often illegible.

In these letters, Ensign’s passion for explaining where the churches went wrong and were dividing people, and how the medical world had been corrupted by the pharmaceutical industry.

His ideas about exercise, eating well and relying on whole foods sound standard today, but all of these ideas were ahead of their time.

Jon explains, “He sensed that the times were ripe for revelations from scripture to come out. He was not a political person but felt that the government, like the churches, had taken wrong turns and divided people. He believed that citizens needed to come together, survive together. No one should presume they are more important than others. Dad had this message of humility. He saw it as a global movement, a simple message he’d repeat over and over. That message was that everybody and what they had to say was just as important as anyone else.”

Sauvie Island's wild natural environment draws my family there in the winter months, particularly when the Snow Geese winter there in the thousands and the beaches provide miles of clean, untrammelled walking territory.

A

few months ago, I interviewed experts about what it would be like to survive in the Pacific Northwest during societal collapse brought on by climate change, and also, how the Pacific Northwest might evolve as we find ways to engineer ourselves out of catastrophe.

But Richard Ensign seemed to have a premonition for such a possibility forty-five years ago. He was answering a question few of us are asking today. How will our children and grandchildren survive a collapsing world? In doing so, he became a pioneer of small space living, thirty-five years before the global popularity of the tiny house movement. He proved that anyone can engineer their way out of, and even thrive in a coming collapse.

Ensign’s son told me that his dad would have been perfect for the internet age, where he could share his vision of his global movement. But actually, has the age of the internet maybe made us less inventive, less original, less bold, more attention-seeking? Is it making our ideas more like everybody else’s? More safe?

Two of my high school buddies have built their careers around experimenting with climate-friendly renewable energy. One is building bicycle-powered batteries in Africa, and the other experimenting with airborne wind power. So proud of them. But we need more people like that, these days. More people like Richard Ensign—bold, visionary tinkerers of the future.

Viewing Washington state from dual portholes on Richard Ensign's 31 foot trimaran boat. Portland graffiti artists are known to leave the artwork of prior artists alone, meaning that the original artwork remains largely untouched.

Steel Drum Genius on the Portland Canal

I

n the fall of 1993, Richard Ensign left Oregon altogether, and settled near Hyder, Alaska, an unincorporated village, population 87.

While Hyder is technically a U.S. village, it is so isolated from any United States center that it uses Canadian currency and relies on Canada for nearly every resource. Richard Ensign had designed and built a floating home in Oregon, and then assembled it in Hyder, where he docked it on water in the Tongass National Forest in the nearby Portland Canal, a 130 mile fjord cutting deep into southern Alaska and British Columbia.

He lived off of moose and bear, which he shot himself, curing the mustard-pickled meat in 50-gallon steel drums.

A scan of Richard Ensign's letters to his son, written on the back of restaurant napkins from his new home in southeastern Alaska.

D

uring these years, he began to feud with the National Park Service, which was always on his case. He saw that he had a right as a senior citizen that had contributed to this country to live as he chose, to live off the land, and be free.

In his journal notes, Jon ponders, and comes to grips with his unique childhood: Our parents teach us the best they can and we must learn to discern what they mean, to read between their words, to understand their motives and to accept the circumstances of their lives. We are born with a need to love and to seek beauty, to appreciate beauty, to teach and to encourage.

Supplemental Information on the Sauvie Island Saucer Boat

Koin Local 6 News Story

Koin Local 6 Follow-up Story

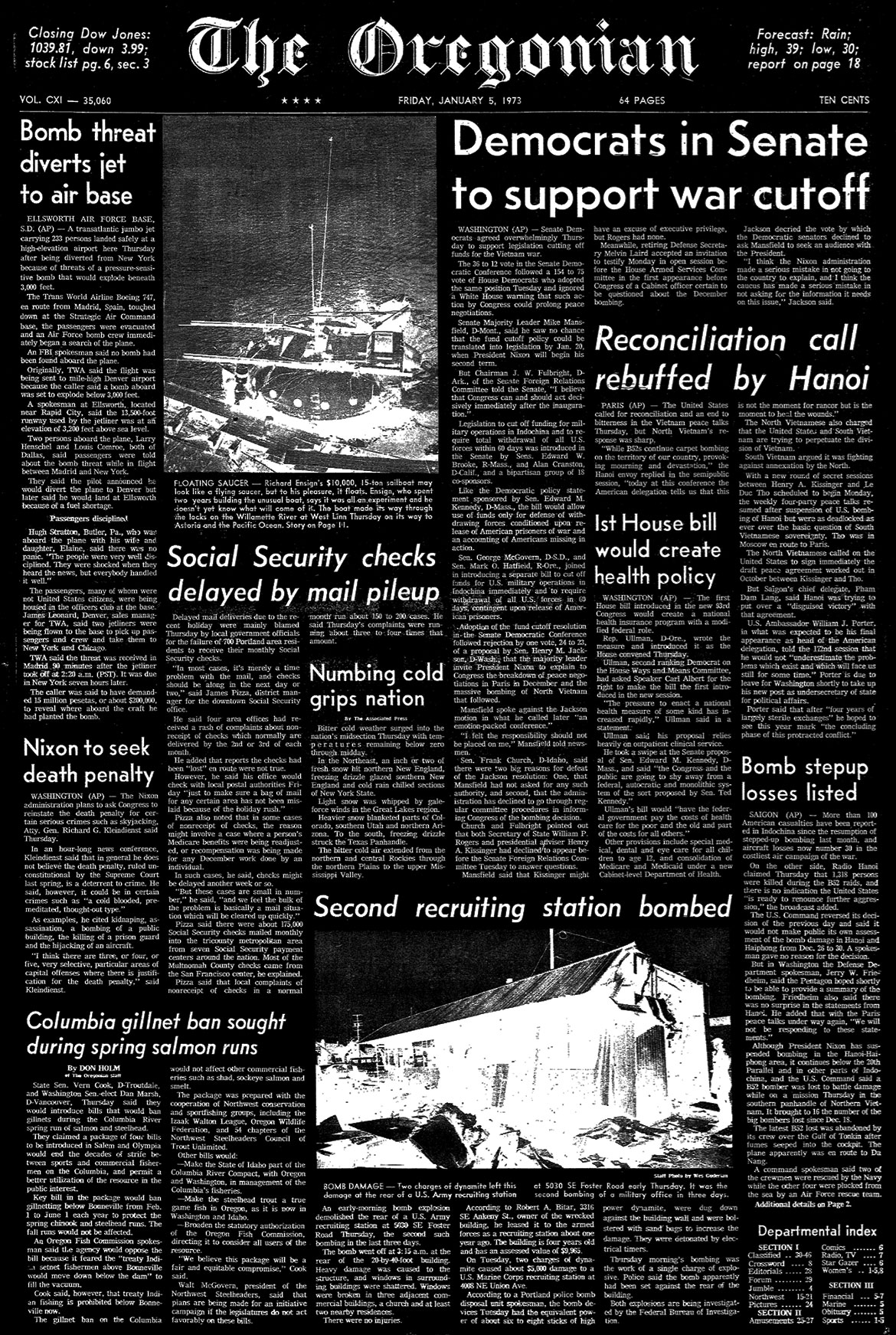

The Oregonian, Friday, January 5, 1973

The maiden voyage of the boat was covered by the Associated Press, as well The Oregonian. Here is page one of The Oregonian from January 5, 1973.