Neotropics

Scarlet Starsong on the

Tambopata River

Notes on perception through the lens of synesthesia, and the value of global biodiversity, from one of its prime hotspots in the Peruvian rainforest.

Turn off your headlamp on an overcast night, alongside the Tambopata River in the Southeastern Peruvian province of Madre de Dios, and when your eyes adjust, you see that the forest glows in the light of its own organisms---glow worms embedded in a cliff shine like stars, fireflies flicker, mushrooms resonate softly, and leaf litter fungus gives off a faint pale bioluminescence.

I am drawn to places that pulsate with life, and this western perimeter of the Amazon Basin, this wild network of Amazon tributaries which form at the eastern edge of the Andes, is ground zero for biodiversity on Earth.

I am hopping a network of three lodges to the Tambopata Research Center, six hours upstream from the port near Puerto Maldonado. I hope to ask, and maybe even answer, some questions about the meaning of places that contain mega-biodiversity. What does it really mean, and why is biodiversity important?

From the Refugio Amazonas lodge, about two hours upriver, I walk down a small path with a handful of tourists, guides and naturalists, and step onto a riverboat.

It's been raining upriver, at the river's origins in Bolivia, and in the isolated and nearly uninhabited protected zones to the south. That means the riverboat pilot, who communicates with the captain from the front, needs to be extraordinarily vigilant; the river is already raging, and islands of logs are rushing downriver.

Map Tree Frog (Hypsiboas geographicus) hunting at night along the Tambopata River.

I ask Saay, who I hired as a jungle guide under contract with Rainforest Expeditions, about the Ceiba tree to the right of the river. At nearly 200 feet, the tree towers above the rest of the rainforest canopy.

The trunks of ceiba trees rise straight up without branches, and form a grand umbrella, providing imposing shade beneath. In the darkness of the tree's upper limbs, you can make out a silhouette of orchids, heliconias, oropendola nests and vines. It is deep in the shadows of this umbrella that Peruvian tribes imagined Gods to dwell.

Hearing Saay's reply, a jungle tourist in the seats ahead of us turns around. Clifton is wearing a khaki shirt, sport sunglasses bound by Croakies, and technical pants that zip off into shorts.

"When we were in Africa," he says, looking out at the tree, "we saw these giraffes. They are so tall, they could eat the tops off that tree."

"They weren't that tall, dear," his wife says, challenging him.

He looks at the tree, "Maybe not. But maybe. Those giraffes are really tall."

It's going to be a long trip upriver, so I put my feet up and rest my binoculars on my lap, and looking out into the jungle, I sleepily imagine a tribe of 200-foot tall giraffes; double the length of an adult Blue Whale, wandering carelessly along the banks of Amazonia.

It is in this sleepy state that, in my head, the sepia and ochre hues of those imaginary giraffes give off both numbers and letters. I perceive the giraffe kind of like this: 13-26-13-26-13-26-13-26, as well as HD, HD, HD, and so on and so forth, all the way down the length of that ceiba tree. For most of my life, I had thought that this way of seeing the world was how everybody else saw it.

About a year ago, I was driving west back home in Oregon, and an NPR interview was playing on the radio. The interview subject described this condition that affects about one in a hundred people.

I slammed on the brakes and pulled into a gas station. Into my phone, I typed a phrase and found the definition of synesthesia, and suddenly I understood something about how I have perceived the world my entire life.

Synesthesia comes in many forms. To some people, sounds have taste, or musical notes have color, and others perceive points in time as floating in space. For as long as I remember, numbers and letters emanate color, and words are like little palettes of paint, dates, weekdays and months have hues. Regardless, in anybody who has synesthesia, there is a level of mental crossover, or union, between our senses.

Today, I understand the power of my synesthesia on my travel to the Peruvian Amazon, and how it influences the way I see this place.

We stop at a small river island to look for macaws. Saay notices river water flooding gently onto the island, and suggests we just leave our boots on the boat. We cross the muddy island with a group of jungle tourists, many who have come all this way just to see the extravagant birds.

Some comment on my bare feet. "Is that just your style?" one asks. Another, "Watch for fish up your urethra!" referring to the Amazon tall-tale of the candiru fish, which climbs into your privates.

But as we approach the other side of the island, I get this feeling that the entire island will soon be underwater. Saay and I bird the clay licks in our bare feet, the river water pooling at our feet, while others, in their boots, are forced further and further back.

Good call, Saay.

A Coreidae Leaf-footed Bug near the Posada Amazonas Lodge, Tambopata River.

Arriving at Tambopata Research Center

On most days, there is a fifteen foot staircase to climb from the river to the path through the forest that leads to the Tambopata Research Center. Today, the rains have completely drowned the stairs. By tomorrow, I'll walk down the complete staircase to get back into the boat.

The Tambopata Research Center is one of the most remote lodges in Latin America. It lies in the center of a dense, well-preserved forest that, like so many other Latin American jungles, is threatened from every side by oil exploration, gold mining, and the construction of the Interoceanic Highway, which will connect Brazil to Peru directly via the Madre de Dios rainforests.

The research center hosts the Tambopata Macaw Project, a long-term research project focusing on the ecology and nesting habits of the iconic birds.

The macaws, as well as the lure of a potential big cat sighting, draw tourists up the river, and as tourism grows, so does the justification to expand the protection of the wilderness.

In this way, species like macaws and jaguars serve to protect something much bigger; a slice of biodiversity. The fact that there are people all over the world interested in seeing magnificent birds and cats is a wonderful thing, as is the way that tourism can act as such a powerful tool in protecting tracts of land.

But how would we protect land if we were motivated purely by the concept of preserving biodiversity itself, and if we truly understood the benefits of doing so? Is it possible for us to look beyond the tourist dollar or the flagship species, and say that what we're really trying to protect are the ants, the beetles, the bacteria, the fungus and the frogs?

A Cephalotes species of Gliding Ant.

Gliding ants, first discovered in Peru, use a parachute-like behavior to control their fall from trees and move between trees.

Several groups of ants around the world have independently evolved this behavior.

Rivers of Ants and the Antbirds who Follow Them

Soon after arriving at the small lodge, Saay and I boot up and head out.

One of the first things you see when you walk into the neotropic forests are the leafcutter ants, scurrying across logs and vines, carrying chewed leaves off to the deepest interiors of their underground nests, where the material is processed into a substrate for cultivated fungus.

The ants survive off this staple crop, but in order to keep their fungus healthy, the leafcutter ants have developed another strange symbiosis; the ants actually grow a bacteria on their bodies which secretes chemicals that keep the fungus healthy and free of various pathogens and molds. These strains of bacteria, which the ants have utilized in their farming techniques for 50 million years, are the same we use for over two-thirds of our antibiotics and cancer-fighting compounds. Scientists believe the future of antibiotic medicines lies in the biology of this symbiotic relationship.

Scientists also believe that the compounds of the future; the materials of industry, technology and medicine, lie in the secrets of unknown or unstudied species. In the Latin American jungles, some random ant, some fungus, some bacteria, or arachnid will contain answers to the advancements of our future.

As we walk deeper into the forest, the mud gets thick, to the point where we're walking through pools of brown water and tugging at our boots to pull free with each step.

Around the rims of these pools of mud are lines of ants, moving quickly. And it is easy to see an individual line of these ants as being like the lines of leafcutters - a column of organized industry. But if you look farther into the forest, you'll see that these columns are actually everywhere, and they are all headed in the same direction. This is an ant that is not headed home. No nests to crawl into, no cavities to rest in. The army ants are in constant motion, perpetually moving, raiding, destroying everything in their path.

This is all good for Saay and I, because we had agreed to spend the better part of the day antbirding. Wherever you find army ants, you will find birds, many of which are often those related antbirds, anthrushes, antwrens, antshrikes, antvireos and antpittas. These hundreds of birds tend to be drab, adorned in the dark hues appropriate for the dense, dark understories of Latin American forests.

As army ants storm an area, they leave the carcasses of their prey behind, creating constant opportunism, and a niche, for a mad diversity of birds, and so, mixed-species foraging flocks are in constant pursuit of these columns.

The flocks are often there, not far from you, but you can't see them. They are often nearly invisible, and sometimes even silent. Because of this, antbirding can be immensely frustrating, and, as Saay explains, "lonely, and even boring, when you're out there by yourself, but when there are two of us, it's exciting again."

The pursuit of antbirds is to isolate something out of the chaos of the environment; a visual puzzle wrapped in the sweat and effort of jungle hiking. It's chaos and confusion into order, clarity and beauty. There are few views of Earth as spidery and three-dimensional as the view from the understory of a jungle. For a synesthete, all this structure of vines and buttresses, patches of light and vast swaths of dark comes with some extra inputs, because our senses are cross-talking through the experience.

Non-synesthetes wonder about the noise of synesthesia; how can you concentrate with all that background noise? But this is like a person who sees in black-and-white saying the same to someone who sees in color. Since we were born with these crossing paths, we know nothing else.

I guess now, I understand enough about it to know that we synesthetes were meant to use it as if it were a gift.

Antbirding is particularly difficult for people from North America. We're used to the visual cues hidden among oaks, maples and pines. Saay has lived his whole life in the Amazon, and his eyes are going to work with him on that observation.

Saay grew up in both countries, and worked in each as a logger.

His job was to carry freshly cut timber along a trail. With a group of loggers, he would lift and carry the wood a small distance, handing it off to another crew, forming a long transport chain through the jungle. One day, logging wrecked his back, and he had to find a new career.

As an English and Spanish wilderness guide, Saay moves between guiding in the Tambopata and in the Brazilian Pantanaal. When he returns home to Puerto Maldonado, he races enduro motorbikes through jungle tracks, sometimes traveling throughout Peru with his friends, following the route of enduro competitions.

Olive Forest Racer moves through the understory.

Swamps, Snakes and Biomass

Back at the lodge, a young man is throwing up. "He's been sick all day. He's crying. He's going to need to get out of here," I overhear somebody saying. That's not an easy proposition; the only way out quickly is to full-throttle back down that raging river, for six hours.

At the bar, I meet up with Clifton (giraffes in Africa), who explains, "he's probably got some e-coli in his stomach. You know, they say that when it rains in the jungle, it pours. And it's pouring on this guys vacation. Luckily, I've got just the right medicine for him."

By morning, the young man will be cured. But, seeing Clifton transformed from bumbling jungle tourist into doctor-in-action reminds me of this incongruity that is on display in the jungle. Here, we have someone like Clifton; likely a successful, brilliant cardiologist, who has trained in medicine for many years, meaning that he has advanced training in a practical form of a biological science. Yet, once he's back in the natural world, he stumbles over the most basic facts of biology. No, there are no chimpanzees in Peru. No, spiders are not insects. No, giraffes cannot eat from two-hundred foot tree-tops.

But Clifton is not alone. All of us tourists at the lodge are capable of revealing our spectacular deficiency in our understanding of the natural world. And, if those of us who have traveled this far to see something of the natural world are largely uneducated about it, what does that mean for the rest of the world? Does it matter whether some guy sitting at a desk may or may not comprehend the value of all these life forms, crawling and slithering about, in the middle of the night, thousands of miles away? How important is it for a global public to deeply understand the riddles of the natural world, and the complex, sometimes invisible threats these far-flung hotspots may face?

Tonight is especially humid, and I have trouble getting my wellies on. We walk out into the jungle on a pitch black night; Tonight, we're looking for snakes, and we walk deep into the forest, down into the lowland, where six inches of mud turns into eighteen inches of stale water.

Plants and vines hang over and grow out of the swamp, and we silently drape each one with the light of our headlamps, as we look for the camouflaged vine-like shapes of snakes in the tangle.

The spiders in this swamp are everywhere, and they all seem to be the larger variety. On four occasions tonight, we pass by brazilian wandering spiders, the most venomous spider genus in the world. In each case, we see the animal and adjust our path.

Banded Cat-eyed Snake prowls for treefrogs in swampy lowland terrain.

Finally, a snake emerges. It is a Blunthead Tree Snake, with large slit-pupil eyes and a body as slender as a scallion. Both arboreal and nocturnal, the silent and elegant creature moves through the trees with an otherworldly grace. If simplicity is the ultimate sophistication, then the Blunthead Tree Snake is the most divine sophisticate - just a string with big eyes at the end, and a coat of rhythmic white and amber.

There are 60 snake species in the Tambopata region of Peru, and in some ways, the Amazonian rainforests of this part of the world are often considered synonymous with snakes - so much so, that you could almost imagine them to be lurking underneath every branch. But snakes, like any other larger animal in the Peruvian Amazon, are scarce. And this is an important lesson about biodiversity: if you would measure the mass of all the living things in a forest, or rather, measure its living biomass, you would find that the apex predators, like jaguars, caimans and even snakes, account for just a tiny fraction of that total biomass.

Each level down the food chain, from the apex predators through various levels of consumers, like mice and birds and insects, down to the primary producers, like grasses and algae, you'll find that the total biomass increases substantially at each level, like a pyramid. In order for each level to thrive, the level below, naturally, must be thriving.

If you consider only animals, then the soil creatures, earthworms, ants, termites, and all other insects account for over 85% of all animal biomass.

But if you add up all the plants, their total biomass comes out at a thousand times that of all the animals in the world.

It gets even crazier with mushrooms, and other fungi, which contribute 25 percent of the world's global biomass.

Chestnut-eared Aracari in lowland canopy at Posada Amazonas.

But once you look at the copepods and cyanobacteria in the ocean, and the world's prokaryotes, or bacterias, the math gets even more profound. The biomass of these organisms overwhelms everything else.

It's true that animals like jaguars, macaws and snakes are important to the ecosystems they inhabit. The reality is that if push came to shove, if we lost many of these primary consumers and apex predators, the world would move on, and adapt.

It's these lower levels, where diversity blossoms into the millions, and biomass explodes into incalculable numbers. And it's these lower levels that create everything about our world that makes it liveable. If the world's bacteria, fungi, cyanobacteria, plants, and countless copepods of the oceans begin to disappear, then so does everything else.

There are some cases in the world where biomass surges in an apparently simple ecosystem. Antarctic krill, tiny crustaceans of the south pole, are believed to have the single largest biomass of any one animal species.

But biomass explodes where biodiversity is rich. A good way to think about this is to think of a big, productive, wealthy city with a large GDP, like New York or Tokyo, and compare it to a place that is financially successful due to a small number of economic inputs, like oil and natural gas boomtowns in Texas or North Dakota.

In the big productive city, where the tall buildings may be representative of trees filled with various ecological specialists, you have a complete economy - from street vendor specializing in catering to a very specific niche of the economy, to the apex mega-corporation, broadly affecting the health of the entire region.

There are a few places in the world that are the ecological equivalent of New York and Tokyo, and they tend to look very much like the forests of the Tambopata River. These are the megadiverse hotspots of the world; they exist in Papua New Guinea, the Congo, and in Indonesia, for example. But most of these hotspots are centered around the perimeters of the Amazon - in Peru, Ecuador, Venezuala, Colombia and Brazil. The Peruvian Department of Madre de Dios, which contains both the Tambopata and Manu regions, is unparalleled.

Moth species lapping at plant sap in the Tambopata rainforest.

Donald Trump Caterpillars and Crying Turtles

After returning from the swamp, I want to know: why didn't we die from those brazilian wandering spiders?

I meet Aaron Pomerantz, an entomologist from Southern California who has been hired by the Tambopata Research Center.

"They have no reason to risk themselves by biting a large mammal," he explains. "Wandering spiders will do everything they can to avoid you. It's almost unheard of to see these types of spider bites in the jungle. More often, wandering spider bites happen at farms."

At night, wolf spiders are everpresent in the Tambopata rainforest.

I ask him about his unusual position, which allows him to literally walk out into the woods in search of new and interesting species.

He explains, "First, a decoy spider was discovered in the area. Then, a macaw researcher found the first Silkhenge Spider. The Donald Trump Caterpillar, which looks like Trump's mop of hair, came out of Tambopata. And of course the famous butterflies drinking turtle tears, which only happens here in the Peruvian Amazon, because of a sodium deficiency in the water."

"What first drew me to this particular area was the discovery of the decoy spider. I think that this discovery made it click for the Tambopata Research Center that there are lots of arthropod discoveries left to be made, and that the public finds some of this stuff really interesting if it is presented well. This has sort of created a unique science-marketing combination position here. The discoveries can help promote tourism because when a story goes viral, it's a form of publicity; it can interest people who may not have thought about coming to the Amazon before. This can help promote conservation because tourism supports the infrastructure needed to maintain the Tambopata National Reserve and the scientific publications that come from the discoveries help to add to the body of knowledge about the biodiversity - trying to claim that a region should be conserved is much harder when you don't have studies backing up what biodiversity is actually present in the region. "

I ask him about his recent find of a strange symbiotic relationship between a butterfly and ants.

He explains, "My colleague and I noticed that butterflies were hanging out with ants on bamboo shoots. This was odd because normally ants just rip adult butterflies to shreds like any other invader on their food source. We then found that the ants also take care of the caterpillars; they protect them in return for a sugary food source produced by the caterpillars. This mutualistic relationship is known as myrmecophily and while it is known to occur for caterpillars in this family, this is the first time it has been observed for this particular species and we still think it is unusual for adult butterflies to interact with ants this way."

A Eumastacidae monkeyhopper along the Tambopata River.

A Decoy Spider

The next evening, Saay and I boot up again and head out in a new direction in the jungle. Our plan today is to follow the river downriver along a series of trails, looking for poison frogs in the last hours of light, and then to continue at night, switching our focus to lowland terrain.

I try to find the local poison frog species wherever I go, as I know of few creatures with such vivid and expressive colors. The local poison frog in this region is the Three-striped Poison Frog; black with brilliant lime green stripes. But after countless hours of looking, we cannot seem to get anywhere.

We work hard all evening, delicately scanning the tangled root systems of palms, and peering underneath logs.

As we grow more and more desperate for our poison frog, we walk deeper and deeper into the forest and come across an area where a giant tree had just shed its scarlet-colored petals. For as far as we can see, the jungle floor has been coated with intense color.

"Saay," I say. "Let's give up on the poison frog. We've been looking for days. Let's just take a break."

We each pocket our headlamps, dimming them, and in this darkness, while sipping water, for the first time I can really hear the sounds of the jungle. Saay explains that locals call the scent of these flowers, the 'scent of the mother of the jungle."

The fluttering rhythms of crickets and the cries of frogs and birds creates a sound that is almost song-like. Through an opening in the trees, I can see stars twinkling, and the synesthete in me blends those senses, so that I imagine the stars singing a song of scarlet, a lonely, quiet song to the jungle mother, out here along the Tambopata River.

We begin to walk again, although now without talking.

As a synesthete, I hunger for this idea of finding something simple in a complex world; of wanting to find an answer of order out of chaos. I have this habit of wanting to project ideas out into something resembling an infographic, where I assign the different colors and textures to ideas. Sometimes, I prefer to imagine different ideas as colored blocks, and sometimes I will stack related issues on top of each other, perhaps in a way that might look similar to the Food Pyramid.

Tonight, I am thinking about biodiversity, and whether it really is important for us to have some understanding of it, and what it means for us.

An issue that rests on the very top of this issues-pyramid might be extremely important to the success of a people, but it sits at the top because other issues must first fall into place for a group of people to thrive or succeed at that issue. I might think that education sits up there at the top, or even a complex public good such as protection against global disease outbreaks.

Anybody can quibble about which issue gets stacked above which issue, but is it possible that there is one foundational issue to which nobody can refute as the single issue that precedes all others?

What's more important, the economy, or national security? The rule of law? Tax policy? Public debts? The gap between rich and poor? Education? The economy is often cited as our most important issue. But there are other issues that are foundational to the economy. You can't have a good economy unless you have the rule of law and national security.

But what's foundational to all of those things?

Small, brilliantly-colored orbweaver spider.

Our planet's life has evolved for 3.5 billion years. As organisms on Earth have evolved, our inorganic Earth surface has changed along with them; a by-product of all these organisms interacting with the surface of the Earth. Because of this, our Earth's surface - our atmosphere, our oxygen levels, our oceans' salinity, have themselves changed; resembling relative stability and favorable conditions to our planet's life. It appears sometimes as if the animals and plants have influenced the Earth to co-evolve with them. Whether there is any validity to that can be debated; but no one argues that the conditions of the surface of the Earth; the very building blocks of life on Earth, were not created by the history of evolving life on Earth.

For most of history, we considered the air we breathe and the resources we consume and the health of the natural world for granted. I'll propose that the concept of biodiversity - the degree of the variation of life on Earth - is the baseline issue upon which all others rest. A healthy, biodiverse ecosystem literally creates the foundation for the very essentials we require to live and thrive.

In this way, you could argue that preserving biodiversity, or rather, upholding human institutions which preserve the world's biodiversity, is the fundamental foundational role of the human in the modern age.

A Heliconius Butterfly roosting on a vine in the Tambopata rainforest.

When you think of biodiversity, don't think of macaws and jaguars. The biodiversity that matters most are creatures of types we have never heard of. Think of the creatures that make up the organic material of Earth - the thousands of beetle species, ant species, the hyphae of thousands of mushrooms and other funguses, weaving through living soils that are homes to countless bacteria, arthropods, nematodes and protozoa.

When you think of biodiversity, don't think of the orca. Think of the coccolithophores, the foraminifera, the tiny crustaceans and molluscs.

Recently, we have learned that an excess of carbon in the atmosphere is acidifying our oceans. This acidification breaks apart the calcified bodies of the tiny creatures that sit at the bottom of the ocean's food chain. As ocean acidification continues, the life of our world's oceans will be left devastated.

Like ocean acidification, the threat of climate change is created largely by human carbon emissions.

Throughout the history of our planet, the carbon in our atmosphere has played a fundamental role in the course of life on Earth. Many of our great extinction events are a consequence of relatively rapid carbon events.

But nothing in the last 800,000 years even comes close to the rapid increases in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

In the media, we are sold climate and ocean acidification stories as being about polar bears, or sinking cities, or crops drying out. What if we could talk about these modern plagues differently? What if we saw these issues first and foremost as threats to our biodiversity - the fuel and the economy of everything on Earth.

Suddenly, Saay spins around excitedly. "Erik!" he yells. "Decoy Spider!" It's only the second one he has ever seen. The spider is a true gem of a find here, largely because the discovery of it resounded globally across the web when Aaron Pomerantz's predecessor, Phil Torres, discovered that the unusual specimen at the center of a web wasn't a spider at all.

Saay and I are looking at a phony; a spider made of debris and insect-parts.

"Where's the real spider?" I ask.

Saay puts his finger up to the inch-long spider decoy, and there, peering out from one of the fake legs, is a tiny whitish spider, completely unremarkable looking, like a plotting man behind the curtain.

The fake spider, whose legs always point downwards, is large enough to resemble the many larger, venomous spiders of the jungle. It's an effective deterrent to would-be predators.

The popularity of the decoy spider on the internet - passed around in Facebook stories, and on sites like Wired.com and the Huffington Post - has helped an innovative lodge draw attention to itself. But that was back in 2012. Since then, many of the big entomology-wonder stories of the internet age surfaced at the Tambopata Research Center.

If we're quite uneducated about biodiversity science, then the use of these strange new discoveries is refreshing.

Grasshopper Nymph at the Posada Amazonas Lodge

The next day, we find one of the silkhenge structures that sent the internet into a fury the next year.

When I speak with Aaron Pomerantz again, I ask him, "Let's say a small piece of forest is lost, and because of that, we lose an isolated species of butterfly or moth, or bacteria or fungus. Why does that matter?"

He says, "If you look at it on the small scale. If you lose a species, maybe that one species doesn't matter that much. But, we live in the most technologically advanced times, and in this age, biodiversity is being destroyed. Its not so much that we lose a species, but that we are losing a species every day. Our forests are being cut down. As you know, we are in what scientists call the sixth mass extinction. We know it, and we understand its consequences, but this issue is not flowing down to policy. You cut out an island of clear-cuts, and you lose the ecosystem. The thing about insects and arthropods is that they are the primary feeders in the forest. Lots of things are happening in the forest. Things are dying, things are decaying. You've got mice, you've got flies, breaking all this stuff down. These are the detritivores. And then you have these primary feeders, which feed on things like plants. Of course, there are the things that feed on them…the apex feeders. But the thing is, the little guys ultimately hold them all up."

I believed that this unidentified leafhopper was displaying for mates when it flicked its colorful wings in the air. But according to entemologist Aaron Pomerantz, it's likely inserting a syringe-like mouthpart into this plant, stabbing into the xylum. Because the plant is pumping water so quickly up the xylum, the pressure inside the psyllid is immense. The wings are actually flipping up as he squirts out excess liquid.

"So, more lodges like Tambopata Research Center?"

"Ecotourism lodges are okay, but you can't do that everywhere. It works well in the case of Tambopata, but if there were fifty more lodges, it would be a mess. You have to see lodges as just a fraction of conservation. These lodges do a good job, but there needs to be regulations and incentives to grow the economy."

The difference between 17-room lodges, and comprehensive national and international protection of ecosystems and biodiversity, is an immense obstacle. But how can you have comprehensive international protections when even sophisticated environmentally-minded intellectuals, the ones have trouble grasping context?

This was on display in an article by acclaimed novelist Jonathan Franzen, in which he lamented the international focus on issues like climate change, over more concrete threats to, say, birds. The piece, though beautiful written, was torn apart for its many glaring errors of context.

In a well-written rebuttal, David Roberts of The Grist writes,

"So lots of people have a Climate Thing, that one tidbit of info or argument that they read somewhere, or heard somewhere, the thing that somehow resonated with their own concerns and beliefs. It's the thing they latched onto, the thing they know about climate, like the proverbial blind people surrounding the elephant. They build on it and it becomes their Climate Thing.

A Climate Thing is not always wrong, though it frequently is. Just as often, it's a kind of distortion, a lens that magnifies one aspect of the issue at the expense of all others. For some people it's nuclear power. For some people it's about models, how there was no warming when the models said there would be. For some people it's Al Gore, or solar power, or consumerism, or population, or "I heard that we're basically fucked no matter what," which I've heard more times than I can count.

For Franzen it's birds. His experience of climate change, in his social circles and intellectual orbit, is that it seems to be eclipsing bird-habitat conservation in the minds of environmentalists. And that bugs him.

So that's his Climate Thing. And as with most people's Climate Thing, it's a little eccentric and a little myopic. Take one step back and you see that birds are far more threatened by the combination of fossil fuels and climate change than they are by any other threat, including cats and wind turbines combined. Times a thousand."

Squirrel Monkeys are one of eight monkey species found in the Tambopata jungle.

The missing link is genuine science education about biodiversity. It's not uncommon for me to run across people who believe that evolution of species takes place within a few years, or that entire habitats can rebound, or even that man can manufacture the infinitely complex biological systems of the world.

In the morning, I sit down for breakfast at the lodge. Across from me is a young woman, looking at her food, sprinkling dark matter on a plate of rice.

Katie Mack is a cosmologist, working at the University of Melbourne on some of the most abstract scientific concepts of our age. Having been actively wondering about these questions of biodiversity and science education, I feel lucky to have Katie sitting across from me.

For the next few days, I'll take any chance I can to ask her if she sees inspiration or similarities between the rainforest and her work in cosmology.

At first, Mack is reluctant, denying any similarity. "I'm here on vacation!" she says.

Like Pomerantz, Mack is drawn to science communication, and writes regularly about astronomy, cosmology and her specialty, dark matter, for science publications as well as general publications like The Economist, Slate.com and Time.

Pondering the difficulty of communicating difficult science subjects, I ask her, "How important is it for the general public to understand astronomy?"

"I think most of the benefit of the kind of science communication I do isn't in helping people understand astronomy per se, but in helping people understand how science works and why it matters. So whether or not they know about rock formations on Mars is much less important than whether or not they know why we're looking at rock formations on Mars. An understanding of the structure of subatomic particles is pretty esoteric, but an understanding that we're using the Large Hadron Collider to learn about fundamental particle physics matters a lot."

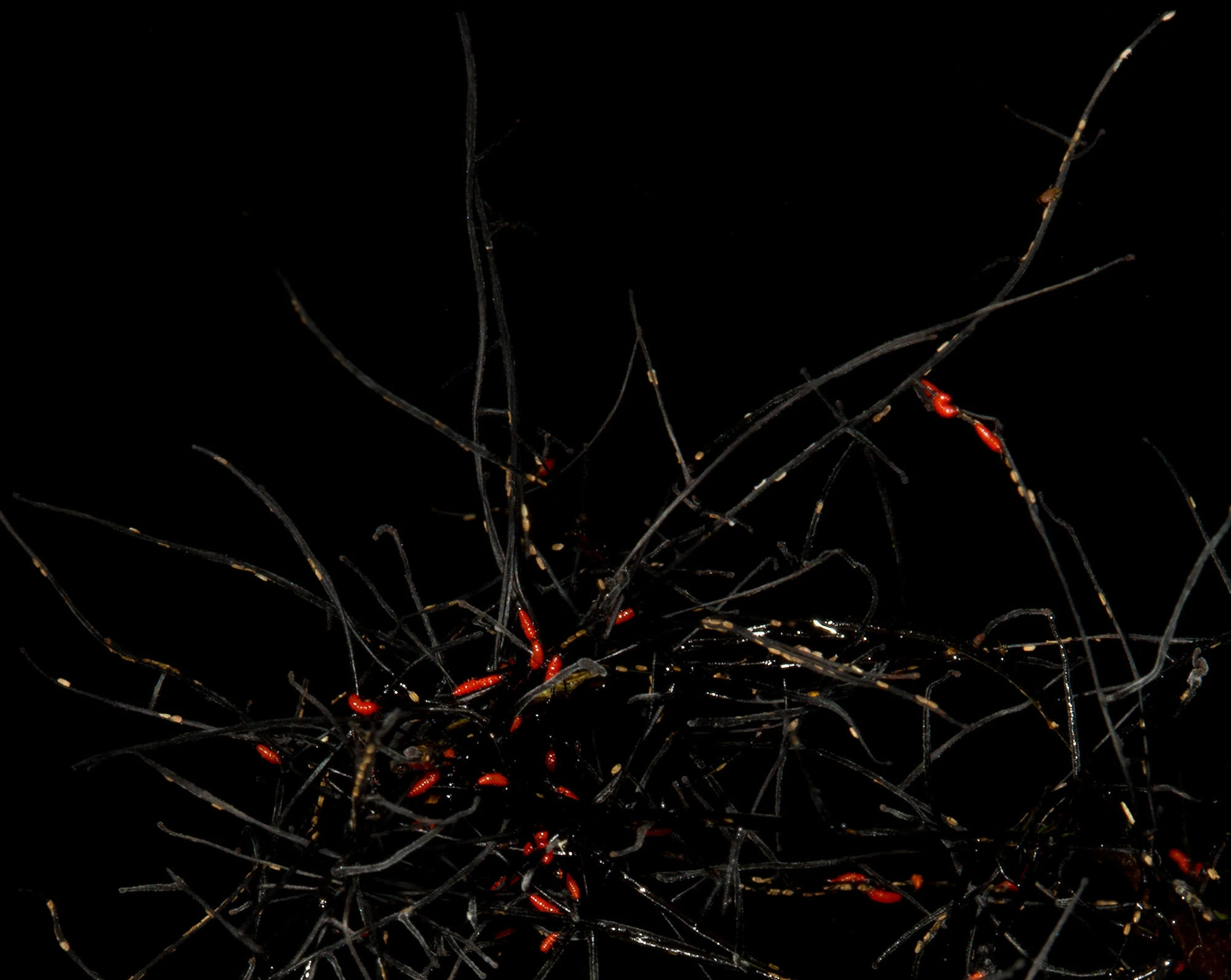

Unidentified fungus and red larvae in the Tambopata jungle.

I ask, "What do you see as the barriers to the public understanding of science issues?"

"I think people often don't trust scientists. We're depicted in the media as awkward antisocial loners, and our work is depicted as incomprehensible. When big results are presented in the media, they're often shown to be the final answer, when they never are, and then people get jaded when they see the 'answer' change over time. So I really think that how we depict the process and practitioners of science needs to change, in a big way. Scientists being more visible and accessible, for example, via social media, can potentially help a lot. But it's also a matter of shifting the popular depiction of scientists away from Sheldon Cooper and more toward the huge diversity of backgrounds and personalities, and genders, you see in an actual scientific research setting."

I ask, "Dark matter must be a particularly difficult subject to communicate with the public. As somebody who has been confronted with communicating with the public about a difficult subject, can you give any advice on making a subject like biodiversity exciting and important to the general public?"

"I guess there are different challenges in the two topics," Katie says, "With dark matter, the problem is that, one, it takes a special kind of physics understanding to explain it and, two, it's very much 'out there' rather than visible and touchable. I mean, it's explicitly invisible and untouchable. With biodiversity, you can make it very concrete -- you can show pictures, for one thing, which is a huge boon. And you can talk about applications for things like medicines and ecosystem health. I guess the similarity is that you have to get people to think about things that are outside their everyday experience and might not in any way affect their daily lives. But for dark matter, I would tend to approach it from the "this is a cool mystery we're trying to figure out" angle, whereas for biodiversity, it's more "we have a potential crisis on our hands and we need to address it -- here's why it matters."

It's good to see this next generation of scientists taking science communication in their own hands, communicating in innovative ways with the public about complex issues.

And while the world's Aaron Pomerantz's are so important in communicating about the natural world, scientists like Katie Mack challenge us to learn about the scientific method itself, which is a tool we need to differentiate the real science from its many imitators in the media.

Three-striped Poison Frog

In the afternoon, I return with Saay to the lodge, only to see a handful of guests waiting for us on the lodge steps. They are giddy for our arrival. "We have a gift for you," the young man who ate alpaca says, and they summon their guide, and we walk back out into the forest.

They issue a small plastic bag from the guide's pouch, and inside is a handful of bark. We crouch down on the forest floor as he dumps the contents out of the bag.

"We found him this morning. We've been carrying him with us all day," one of them says. For a few seconds, the Three-striped Poison Frog sits there, and before he jumps out into the oblivion of the forest, I have a moment to peer at him, 12-7, 12-7, PXX, PXX - glorious, and then, gone.