Great Basin

Road Notes from

John Day Country

A Minimalist road trip through drought-scorched desert canyon roads of Oregon's interior.

The John Day River, which zigzags north and west through Oregon's arid middle, is undammed for its entire length. This makes the river a sort of symbolic character to the state - the John Day is free, wild and unpredictable.

California's suffering from drought this year was well known around North America, but the effect of the same drought on Oregon went largely unnoticed. In Portland, the drought meant sunny days and a warm winter, but beyond that, it was difficult to discern the real impact.

But as you head east from Portland, the visuals of the severity of the drought intensify. First, you see the receding glaciers of Mount Hood, and barren mountain wildflower meadows. As you pass near Warm Springs at the base of Mount Hood, what used to be beautiful desert scrub is now a hundred square miles of scorched earth.

This wildfire started when an outsized recreational vehicle drove along Highway 26 on bare rims, causing sparks to fly for a length of six miles.

A dry summer is evident at Elk Meadows, on the east side of Mount Hood, where wildflower blooms are sparse and views of receding glaciers are abundant.

Part of what makes the Pacific Northwest drought different is that its impact isn't just due to heat and a lack of rain, per se, but specifically a lack of winter snow, the snowpack of which slowly feeds rivers throughout the year, and which fills the reservoirs throughout the state.

It was the second warmest year in recorded Oregon history; the streams are trickles, the docks on mountain lakes sit hundreds of yards from puddles of water, and grasslands are brown.

For most of the year, seeing these things in passing, I still didn't really connect the severity of it all. But as we roll into the small city of John Day in late summer, we see it clearly.

John Day has been converted into command central for the historic Canyon Creek Complex wildfire, which is still raging. Fatigued men in National Guard uniforms are everywhere. Fire-fighting trucks are parked in nearly every lot around the center of town. At the grocery store, the clerk tells me that forty homes have been lost, and sixty-seven thousand acres have burned. "Look south when you walk outside," she says. "That massive plume of clouds you see are not clouds."

Because these wildfires were so well known around the state, many travelers cancelled their plans, of course, further devastating a battered tourism industry.

I think its important not to cancel your plans; it's good to visit places at their moment of despair. To see a place in its worst moment is to see it more clearly, and my memory of John Day is through my memory of weary National Guardsmen and Oregon forest-fighters, sitting around a table planning out their next attack on the fire.

River otters at play in a deep pool on the John Day River.

We have been camping with our friends in rented tepees in a state park alongside the John Day River, just outside of Mount Vernon, Oregon. The park caters largely to RV caravaners, and although the twin tepees are situated upstream from the motorhomes, the park planners thought to place the RV gray-water disposal adjacent to the parking lot for tepee campers.

A lady in her late-fifties approaches us while her husband carefully applies white gloves on his hands. "Did you stay in those tepees?" she says, looking amused. We explain that they were comfortable and that the kids really enjoyed the experience.

The lady starts laughing at this, and saying little things between laughs - so small, so rustic, so cute! I always appreciate the friendliness of RVers, and this nice lady chatting us up is no different. But her laughing, which has now become almost a cackle - can't believe it...tepees! - reveals the classic bewilderment of the American caravaner with those of us who prefer not to drive our kitchen sink and toilet from place to place.

When I hear the husband clamp the gray-water removal hose to their RV, I can hear the sucking and humming of their nasty RV water being drained into underground holding tanks.

A lot of Americans have come to the conclusion that the larger your vehicle, the more pleasurable your road trip experience will be. This is a fundamental flaw of the American roadtripper - and, I've come to believe, the more of the RV mentality you can shed, the better off you'll be.

This summer was a long, dry and hot one in Oregon, which brought out a long season of Oregon road travelers. It gave me a chance to observe my fellow road trippers.

Oak Treehoppers are vivid and unusual insects which appear in Oregon's arid regions at the end of summer. From above, they resemble Mexican lucha libre masks.

From an evolutionary standpoint, these demonic mask-shapes likely make the insect look like a small snake about to strike.

Years ago, if I saw a big van or truck loaded up with kayaks, canoes and bicycles, it would fill me with happiness. If I saw an RV with lounge chairs strapped to its top, and a fishing boat in tow, I would be ecstatic.

And in my own road trip packing, even if I thought I was packing light, I would fill the car to capacity, and then go for the rack straps.

As I downsized to a two-door Jeep this year, and forced myself to rethink what I used to think was light packing, I paid more attention to how other roadtrippers packed. I also noticed that more often than not, it was those over-stuffed cars and vans that were parked on the side of the road - overheating, blown-out tire, or just time to re-tie the gear straps.

A road trip requires very little gear. When my family travels by car, everybody is allowed only one carry-on sized bag each. Once you set the rule, packing and unpacking is a charm, and there is always extra space. Tents, sleeping bags and camp chairs fit in a soft-cover bag on the roof rack.

Many marshes and swamplands dried up by June this year. I found this Pacific Treefrog in a small damp spot in a dried-up marsh.

The John Day River winds northwest through spectacular desert canyons, and one morning, I rise before sunrise and drive out from our campsite along the winding route that hugs the river. It's early enough that it's unlikely that anybody has yet covered this road. Sure enough, that means the wildlife is out, and near the spectacular Cathedral Gorge, I spot animals in a deep pool of the river.

To get a closer look, I swing the Jeep around and park it on a narrow ledge off the side of the road. I walk down to the river's edge, and watch three river otters cheerfully playing. This will be one of my favorite memories of the summer - but it could not have happened in a Suburban, or a Motor Van, and certainly not an RV. Road trips require nimble vehicles.

The idea of a road trip is not to be glued to your car; it should allow you the flexibility to get you away from it. That is the other crutch of the large, overburdened vehicle. Always relegated to RV parks and avoiding city streets, motor homes keep you at bay from wherever the action is your travels.

Experimenting with ultralight backpacking with my son and brother in the Three-fingered Jack this summer

helped me think about the benefits of ultralight road-tripping

.

Another wonderful road trip rule is about packing and un-packing your vehicle. Tell your fellow travelers to have their bags packed at a certain time well before you hit the road - I ask my family to have have their bags next to the door the night before we leave. Because American roads often clog up by late morning, an on-time departure almost certainly makes for more comfortable driving.

Likewise, upon returning from a road trip, make it clear that the vehicle needs to be completely stripped of gear, and all gear stowed, before anybody is allowed to open a house door or check the mail. Walk through the procedure with your fellow travelers. For us, it's: strip the gear bag, separate the laundry, clean the cooler, get all the gear back in its storage place, before the house door opens.

Blue Basin Trail, Sheep Rock Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument.

The less gear, the quicker you can get out on the road more consistently. But once you have your road trip gear shaved down to the essentials, you can add the tools that really do enhance your road trip.

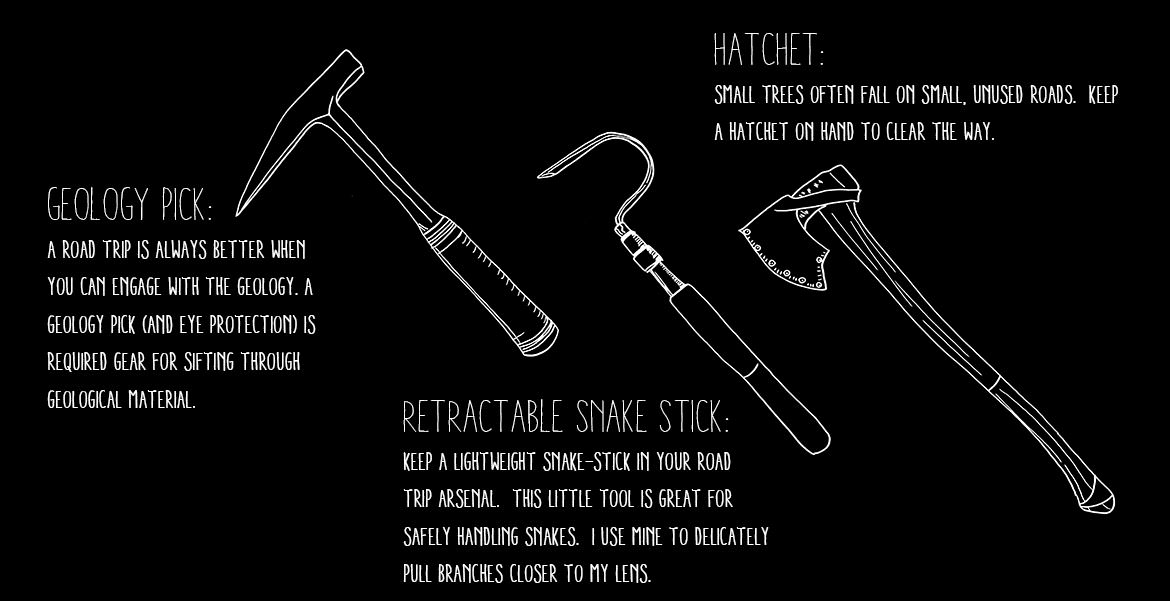

For us, a road trip means getting out and discovering something for ourselves. Most of the extra items we keep in the vehicle - a hatchet, a geology pick, a snake stick, a spotting scope, a cooler, kitchen knife, cutlery, plates, forks, knives, spoons, an aquatainer, battery power - are about either extending our ability to stay on the road without relying on restaurants, hotels and services, or tools that allow us to explore wherever we are more fully.

One of my favorite quotes is from a book on ultralight backpacking. It's a mantra often similarly followed by global travelers, but rarely roadtrippers.

Ryan Kestelbaum wrote in The Ultralight Backpacker, "The old school of thought would have you believe that you'd be a fool to take on nature without arming yourself with every conceivable measure of safety and comfort under the sun. But that isn't what being in nature is all about. Rather, it's about feeling free, unbounded, shedding the distractions and barriers of our civilization—not bringing them with us."